Book Review : “Development, Education and Learning in Sri Lanka : An International Research Journey – Angela W. Little

There are not many authors who can chart the developments of an education system that they, personally, have been researching, supporting and analysing – for fifty years. That gives Professor Angela Little a unique vantage point – and she uses it well.

Not only does she record Sri Lanka’s educational development in that period, but she also surveys many of the most relevant changes in the theory and practice of international education development across that timespan, showing how they both influenced, and were influenced by, Sri Lanka’s example.

Researchers and practitioners alike will value this book for the insights it gives on the unique position Sri Lanka holds in South Asia. A country who achieved a 56% literacy rate in 1948 when India’s was 19%, near gender parity in primary education by 2001, and who, by dint of those things, not only showed other countries what could be done but, also influenced the thinking behind the MDGs and SDGs.

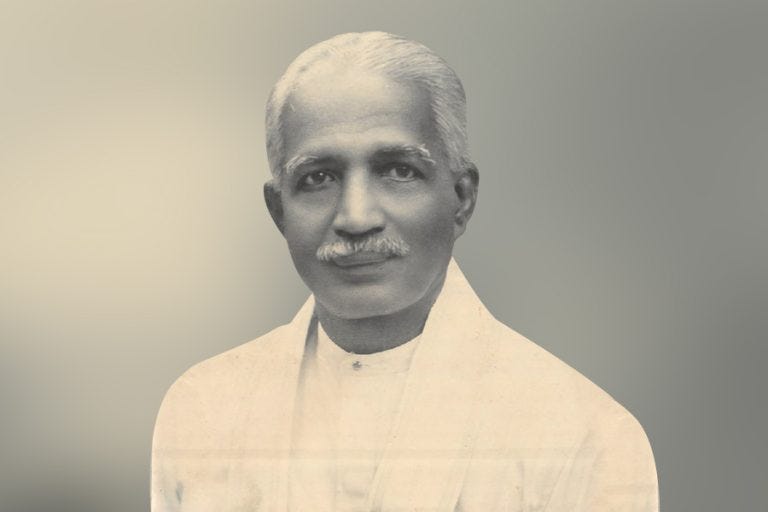

As you would expect from such a helicopter view, historical events and movements come to the fore in the analysis of change. Of all the aspects she singles out, perhaps the most important for the later development of Sri Lanka as a model education system in the region was the personal impact of Dr C.W.W. Kannnangara who, as Minister of Education between 1931 and 1947 played a major, foundational. role in setting the education system on the road to South Asian “exceptionalism” through what Little calls “removing dualities” : language dualities, urban/ rural dualities, cost of education dualities. etc. Notably, Kannangara was Minister of Education for 16 years, and the pre-independence changes he championed all aimed to reduce inequity and increase opportunity for (almost) all. Stability matters.

But, as is demonstrated in later chapters direction matters too and exceptionalism can also go off track. While in the 1990s and early 2000’s the Asian tigers, Taiwan, Singapore, S. Korea and Hong Kong pursued an export-led growth strategy, and benefited hugely as a result, Sri Lanka pursued an import substation industrialisation policy (ISI) which led to anaemic growth and a build up of significant social issues, including educated unemployment.

In its organisation the book is half a retrospective of 50 years of education development in Sri Lanka and half a textbook overview of some key shifts in education development theory over that period : it’s intended to be dipped into with each chapter self-contained. For some readers this might feel disjointed, like two books interleaved into one. For this reader it worked because the theoretical is always related to the practical, or helps to frame the changes being discussed, their origins and their place in wider developments beyond Sri Lanka’s shores.

For example, there is full chapter discussing the “The Diploma Disease” a famous book by Ronald Dore published in 1976. But, it is examined in a way that Dore’s theory as set out, is tested against what actually happened in Sri Lanka (result : it does pretty well, but not perfectly).

The latter sections of the book get into the detail of education change in Sri Lanka in the last 25 years. The imperfect, and often contradictory process of education policy formation, with the tensions of political and technocratic struggles, is well-described both as a researcher-observer and sometimes adviser-participant. One of her funniest anecdotes quotes M.D.D Pieris, Secretary to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education, on the decision in 2002 by then President Premadasa, to announce, mid-speech, free school uniforms for all ! Quoted in full at the end below.

One interesting inclusion is a chapter focusing exclusively on the process of creating national and regional education plans, looking at the many practical issues to be solved, from participation in the process, to language, to the cost of translation services. It highlights too how the navigation of the politics of change cannot be ignored if technocrats value making change happen.

Mentioned frequently is the significant, (and normalised) reality, that for a large part of this period (1983 -2009) there was a civil war going on in the North ; a war between state security forces and various Tamil liberation/secessionist groups, the best known being the Tamil Tigers. Perhaps because it went on so long it becomes a part of the backdrop – while the education system continues to develop, sliding back and progressing in different ways at the same time, though for the northeast this experience is markedly different.

The influence Sri Lanka, and the example of its education system, has had on global education development policies is a unique, and refreshing, aspect of this book. Professor Little’s inclusion of her inaugural professorial lecture in 1988 focusing on what lessons developing countries can have for other countries – in both the global south and north - shows her early interest in this, and she follows it up with a later discussion on how the country’s education development, and a broader conception of what education development means (and how it should be measured), influenced the education MDGs and, even more, the widely drawn SDGs.

For anyone, researcher or professional, with an interest in education in South Asia, this is a very readable book. But, even for those without that specific focus, but who value learning from history, and who like to see education change taken in a fuller, broader and more holistic perspective, this book offers many valuable micro and macro insights.

The book can be purchased, or downloaded as a PDF by clicking the button below.

“A spur of the moment policy decision

… At these functions the secretary had no particular role … except [to] sit there for three hours on the main stage. Therefore, I did not even bother to take my spectacles along … Everything proceeded smoothly until the project minister for education services began speaking. The president’s speech was to follow … Suddenly I saw the president looking back … I quickly got up and went to him. He seemed elated at the largeness of the crowd and their response. He said ‘I want to give free school uniforms to the children from next year. Each one would require at least two sets, isn’t it?’. I was completely stunned, but stammered ‘To all?’. He said ‘yes.’ I had the presence of mind to say ‘but there are 4.2 million children’. He said, ‘in that case we can make it one uniform,’ and continued, ‘Can you work out the costs?’ ‘When?’ I inquired. What he said to this would have killed me if I had a weak heart, ‘Now’ replied the president, ‘I want to announce it in my speech!’ That was President Premadasa. He went on the basis that nothing was impossible and many a public servant was faced with an impossible deadline. This day it seemed to be my turn. I walked back to my seat in a daze … Fortunately one of my accountants who happened to be standing at the back of the stage had with him a calculator … In the end we got the figure of approximately 700 million rupees … I walked quickly up to the president, gave him the figure, but warned him that there could be up to a 20% margin of error. He appeared startled at the cost indicated and said ‘can’t be so much’. The next minute he had to get up to speak, but he was now more cautious. To the vast cheers of the multitude he announced that ‘With effect from next year I will also try my best to give one set of school uniforms free to every child once a year.’ The people cheered so loud and so long the effect was clearly visible on the president’s face, that I knew there was no going back … The die was cast. (M. D. D. Pieris, 2002, pp. 589–91).” Quoted p163.