Re Education : Issue #12 - Futures Betrayed ?

A newsletter about international education development

(If this message does not format properly in your email - please click the “Read in App / View in Browser” above, top right).

Introduction

A new book called “The Political Economy of Education in South Asia” by John Richards, Manzoor Ahmed and Shahidul Islam provides the backdrop to this month’s feature article - looking at why South Asian basic education systems are (with one notable exception) in a dire situation.

Two of the authors (Islam and Richards), reflect on the misaligned priorities of parents / children vs. politicians / bureaucrats. Taking Bangladesh as an example, they highlight some of the poor political choices that have led to a learning poverty rate of 58% despite significantly increased funding in recent years.

They conclude that the dramatic events of August, when the regime was toppled, offer a unique opportunity for Bangladesh to get basic education on track by widening engagement and directing the incentives within the education system to achieving learning outcomes for all children.

Andy Brock, October 2024

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

““You can't go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending.” C.S. Lewis

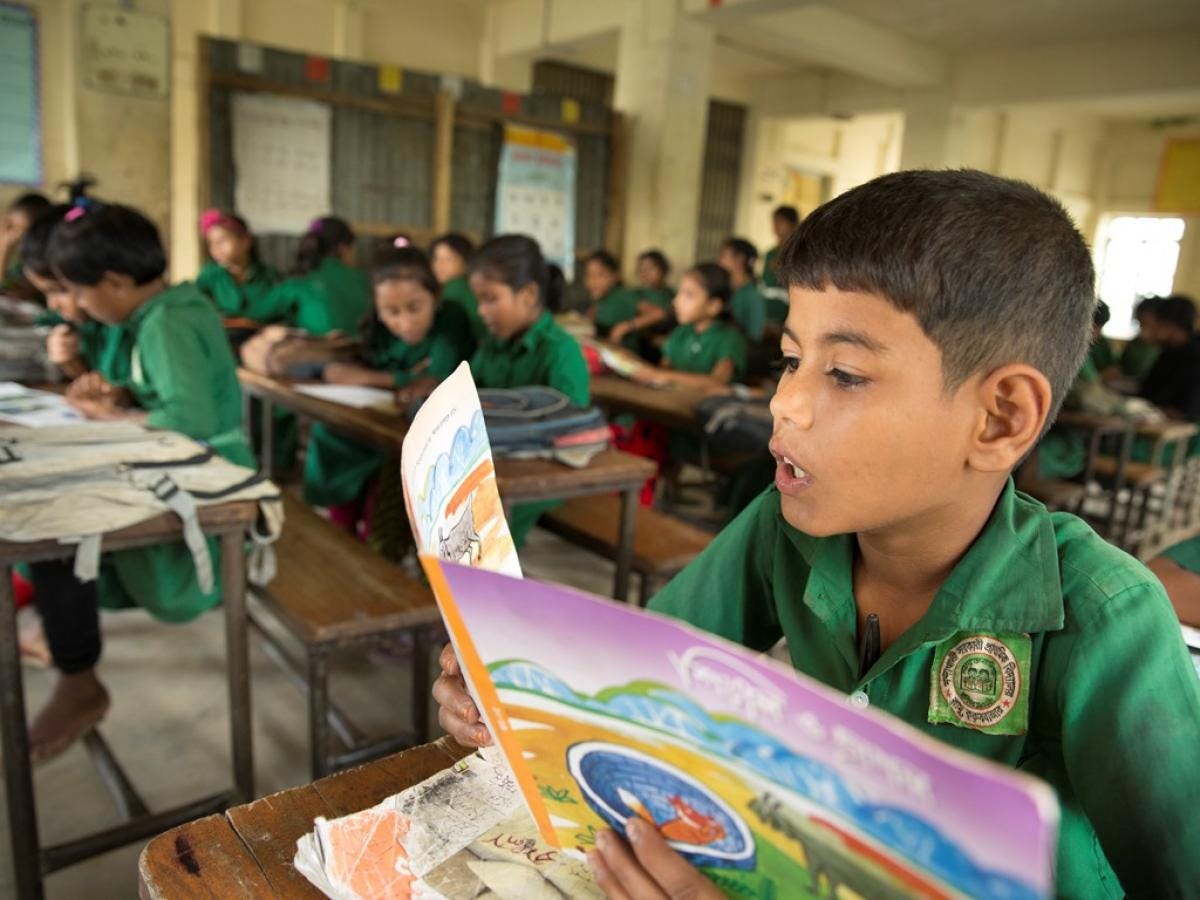

Betrayed : have the children of South Asia been failed by their school systems ?

Shahidul Islam and John Richards

Who does education serve in South Asia ?

Politicians’ goals for basic education in South Asia are different from parents' goals. Politicians want school construction, teacher recruitment, free textbooks, and a centralized system of education. Parents want a quality education that give their children a better future.

It’s no surprise then to see a consistent increase among parents in South Asia sending their children to non-government schools ("low cost" private schools, NGO schools, madrassas) with the hope that their children will learn, at a minimum, the ability to read the local language at a basic level and do basic arithmetic.

But, even in these modest desires, we believe both the children and their parents are betrayed by South Asian school systems—with the exception of Sri Lanka. For example, the "learning poverty" rates in the three most populous countries in South Asia range from 56% in India and 58% in Bangladesh, to 78% in Pakistan. The outlier is Sri Lanka where the rate is only 14%, better than many high-income countries.

Why is this the case given that, over the last three decades, there has been near universal access to primary education ?

To understand this you have to appreciate that school systems are composed of institutions dominated by the education bureaucracy, by politicians, and by teachers' unions. The dominant goal of those groups is not children's learning, but the protection of their own interests.

Gaming the system

Politicians see education as a tool to foster a common allegiance and national loyalty among citizens. That’s why bureaucrats and politicians have gamed universal primary education in various ways. In 2009, India enacted an ambitious Right to Education Act for all children from age 6 – 14. At the same time, Bangladesh introduced the Primary Education Completion Examination (PECE). Both initiatives resulted in higher enrolment and a higher primary cycle graduation. But, not better learning.

The most credible assessment of primary students’ learning in India is ASER, a large-scale assessment conducted at students' homes with a statistically significant sample size ; it’s organized by Pratham, a large NGO. The most advanced questions posed are on the ability of sampled children to read a short story at grade two level and divide a three-digit number by a one-digit number. The national averages of the latest ASER survey, in 2022, are dismal. At grade five, in government schools 39% of children can read the story and 22% can do the division. Though far from ideal, non-government schools perform much better : at grade five, 57% can read the story and 37% can do the division.

But, this begs the question : why are children successfully graduating from school but can neither comprehend a grade two level passage or solve a simple division problem ? The “game” in India and Bangladesh has been to lower the bar to pass the grade five exam, and to frequently allow question paper leakage before the exam day.

As an example, for more than a decade Bangladesh conducted the National Student Assessment (NSA), a very sophisticated in-school assessment on a representative sample of primary school students in grades three and five. But, in 2022, Bangladesh compromised assessment integrity by offering special tutoring to grade five students using the testing tools to demonstrate better performance in their latest NSA. Ironically, the national entity that oversees primary education service delivery played this "game" instead of protecting the integrity of the assessment. The international organization that oversaw the 2022 NSA collaborated with the primary education department in Bangladesh and failed to protect minimum research integrity.

In Bangladesh, despite this kind of scam, international organizations have played an important role in expanding primary education opportunities for millions of Bangladeshi children. Like many other developing countries, Bangladesh has received significant development assistance in education since the 1980s following the elevation of education as an investment emanating from the Jomtien conference in Thailand and the subsequent Education for All commitment to universal primary education.

After 1990, Bangladesh started receiving more development assistance in education. Politicians and bureaucrats used the money to create more positions for more teachers, build more classrooms, distribute free textbooks to all primary school students and expand teacher training facilities. Everything improved except actual learning. After Jomtien, the bureaucracy and politicians met their desires; the parents did not.

Education as investment – for whom ?

Around the world national governments, multilateral and bilateral organizations, have initiated development programs aimed at alleviating poverty. In this development effort, education has always been considered as the single most important means for increasing the household income of the poor. The importance of basic literacy and numeracy is so obvious, and the evidence so overwhelming, that bilateral and multilateral agencies, philanthropies – even private businesses – are all investing in education.

However, the development assistance to education in South Asia has never kept pace with the basic education needs. International organizations put emphasis on quality and equity in basic education and ‘reluctantly’ shared strategies, without adequate evidence, to convince political and bureaucratic leadership to address chronic quality deficits in South Asian basic education.

In Bangladesh, a few development partners tried to include interventions to improve foundational literacy and numeracy in the fourth Primary Education Development Program (PEDP) but their efforts were not concerted and sometimes subverted. The multilateral banks were more interested in disbursing funds than adding any accountability measures to achieve quality educational goals in primary education.

The second PEDP (2004-2010) received 37% as development assistance from 11 bilateral and multilateral donors for a total primary education budget of US$1.8 billion. But, through PEDP 3 and 4 this reduced as far as 8%, despite the absolute value of donor contributions remaining constant, as the government substantially increased its primary education budget.

The government funded this significant increase by negotiating more loans from multilateral banks such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, loans, which would have to be repaid. In effect, additional domestic government revenue mainly served political and bureaucratic goals – not learning goals for children and their parents, which continued to decline. Moreover, the declining donor share of the primary education budgets in Bangladesh reduced their influence in discussions about learning outcomes.

Where now for basic education in Bangladesh ?

Where does that leave Bangladesh basic education, under the new political dispensation ?

Although education will not feature highly among Professor Yunnus’s short term priorities, there are opportunities to change and address the systemic failings highlighted above, not least through a more consultative and inclusive processes.

Undertaking an assessment of students’ foundational skills using the ASER process developed in India is one such opportunity. The results will reveal the scale of the problem and determine how to take action quickly to reduce learning poverty levels.

Investing in teachers is a second essential strategy. Teachers' professionalism and performance are drivers of change in education. A reimagined teaching profession should attract and retain the best talents in the profession, but that also needs changed performance standards, status, incentives, remuneration and career paths. This rethinking about teachers will be a longer-term task, but it should begin in earnest now.

Finally, decentralisation of education management under a single Ministry of Education can open the process of reform to gain stronger traction and wider support. This will be important if a real impact is to be made on foundational literacy and numeracy.

There is a real opportunity now in Bangladesh to stop the betrayal of politicians and bureaucrats. By meeting the demands of parents through focusing on learning outcomes and reforming the education system to accommodate many voices, change can be made possible.

Shahidul Islam is an education policy and planning expert

John Richards is Emeritus Professor, School of Public Policy, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

News

September is conference season. Lots of talk about education, lots of agreement on the analysis, gaps to be filled, the scale of the problem – but, will it all lead to action ? The What Works Hub had a two-day meeting in Oxford in the same week as the 79th UNGA in New York (blog by Ben Piper) – also full of education meetings. Click the links if you want to catch up with either.

So much exhortation for collecting and using evidence – to demonstrate what works and where resources should be concentrated. Has anyone ever tried to quantify the impact of these conferences ? What learning outcomes are measurable as a result ? Perhaps an RCT should be developed – the control could be no conferences for a year !

One of the big launches at UNGA was the International Financing Facility for Education (IFFed), a brainchild of Gordon Brown, former UK Prime Minister. According to its 1-minute explainer video, the IFFed claims to be able to generate $7 of investment in education from every $1 it uses to support countries who are not eligible for IDA. That’s the theory – let’s see how it works : Asia first.

For those interested in UK politics and the impact the new Labour government may have on international development, it’s worth listening to this 45-minute podcast from CGD with Ranil Dissanyake, Stefan Dercon and Laura Chappell. Dercon and Dissanayake also have a new book out called “The Rise and Fall of the Department for International Development”. I’ll be reviewing it soon.

The University of Cambridge Faculty of Education in partnership with UNWRA has released a pithy report (4pp), looking at immediate, mid-term and long term actions to restore education in Gaza. “Palestinian Education Under Attack in Gaza: Restoration, Recovery, Rights and Responsibilities in and through Education”.

Development

Like many educators I imagine, I am, in equal measure, curious, sceptical, worried and excited by the role AI could play in education. So, I was quite bowled over by playing with Notebook LM, a new generative AI service from Google.

I took an old 10-page paper of mine from IJED about the Gansu Basic Education Project (GBEP) and simply dropped it into the software. Ten minutes later it produced this highly listenable podcast summarising the main themes (not perfect, but very good). It’s a bit Californian for my liking (do we say education theories are “wild” ?!), but still, astonishing what AI can do. Have a listen, even just to the first couple of minutes, to get the idea. Try it out yourself here.

Peter Evans, writes a substack called “Not that Peter Evans” and is on a single-minded mission to advance the cause of Political Economy Analysis and banish the phrase “lack of political will”. He did a talk on the political economy of education at the REAL Centre in May and now has a new piece out with (the ever-ubiquitous) Stephan Dercon wondering if there is such a thing as PEA-washing ?

The only trouble is that the phenomenon he describes - commissioning an analysis that you then do not act on – is one that probably describes a vast number (a majority ?) of consultancy / project review exercises. Sometimes inaction may indeed be “washing” (a cynical exercise in virtue signalling), but just as likely inaction can result from organisational power struggles, lack of buy-in, or sub-optimal timing.

USAID has been strongly advancing the fight against lead poisoning and the impact it can have on children. Most of us automatically think of car and factory pollution as the principal cause, but this interesting article reveals another cause and the swift action taken in Bangladesh to neutralise it. You'll never guess the culprit in a global lead poisoning mystery : Goats and Soda : NPR

Voices from the front

In an echo of the film, “The First Grader”, Uganda NTV has reported on the case of a 52 year-old South Sudanese learner who is attending primary school, complete with regulation maroon shorts ! See video here.

Joshua Miskin of Geneva Global posted an interesting piece on a new competency-based curriculum for teachers that he has been facilitating in Ethiopia. The short video in his LinkedIn post, with a candidate teacher, Sara Gemeda, gives a feel for what this has meant for one teacher in practice.

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

If you have any interest in human capital theory and the economics of education (and more educators really should) read this short and brilliant overview of the history of the private and social returns to education by George Psacharopolous, the man whose 1973 book on the subject killed manpower planning and made governments across the world understand that education was one of the best investments a country and an individual could make.

A very interesting presentation by Claire Cullen of Youth-Impact at the What Works Hub conference on A/B testing to improve efficiency of programmes and reduce cost. Making regular small modifications in programmes and testing them led to significant efficiency impacts. This 3-page paper tells you all you need to know. Get half your colleagues to read it - and test the results 😊.

History Lessons

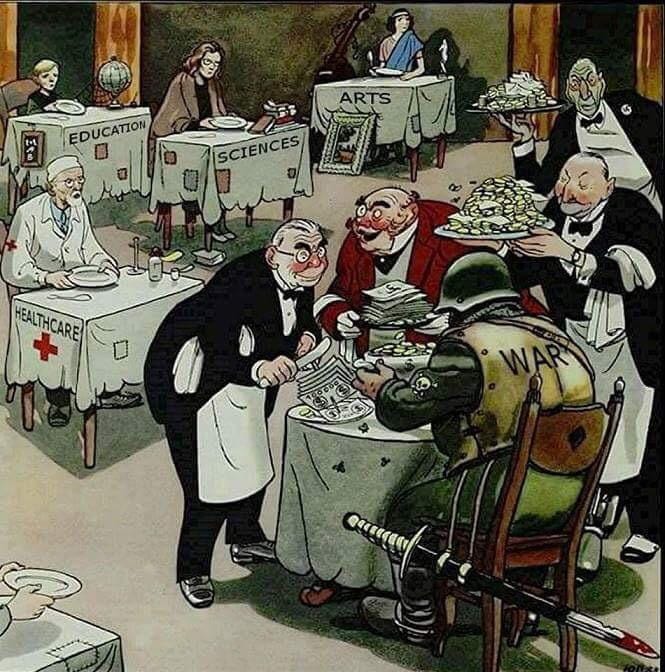

This cartoon, popularly ascribed to the 1920s or 1930’s, is in fact from the 1950s by Russian cartoonist Yuliy Ganf. Sad that it’s so timeless.

…and finally

We’ve just celebrated International Teachers Day - this was one of the best, and truest, posts.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.