Re Education : Issue #14 - The New Digital Divide : AI and Education

A newsletter about international education development

(If this message does not format properly in your email - please click the “Read in App / View in Browser” above, top right).

If the great issue of our age is inequality, AI is becoming the next frontier for digital disparity between the global rich and poor. What can we do to avoid repeating the mistakes of the first digital divide ?

This month’s issue features a guest article by Paul Atherton of Fab Inc. on behalf of AI-for-education.org, a network set up to promote AI in education in the global south. Below, he reflects on the pitfalls, and prizes, that lie ahead.

For all those celebrating Christmas or holidaying I wish you a relaxed and festive season. And for all my subscribers, I wish you peace, good health and mental, physical and financial prosperity (in that order) in 2025 !

Andy Brock, December 2024

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

Good design is intelligence made visible. Le Corbusier

The New Digital Divide : AI and Education

How We Got here

We’re a couple of years into the new AI cycle, and what started with a load of promise and potential has seen new products created, even more ideas surface, and much noise about how it’s going to revolutionise the world. AI is everywhere in high-income countries – with billions of dollars thrown into ‘start-ups’ and the big tech in the US, Europe and China fighting for pole position.

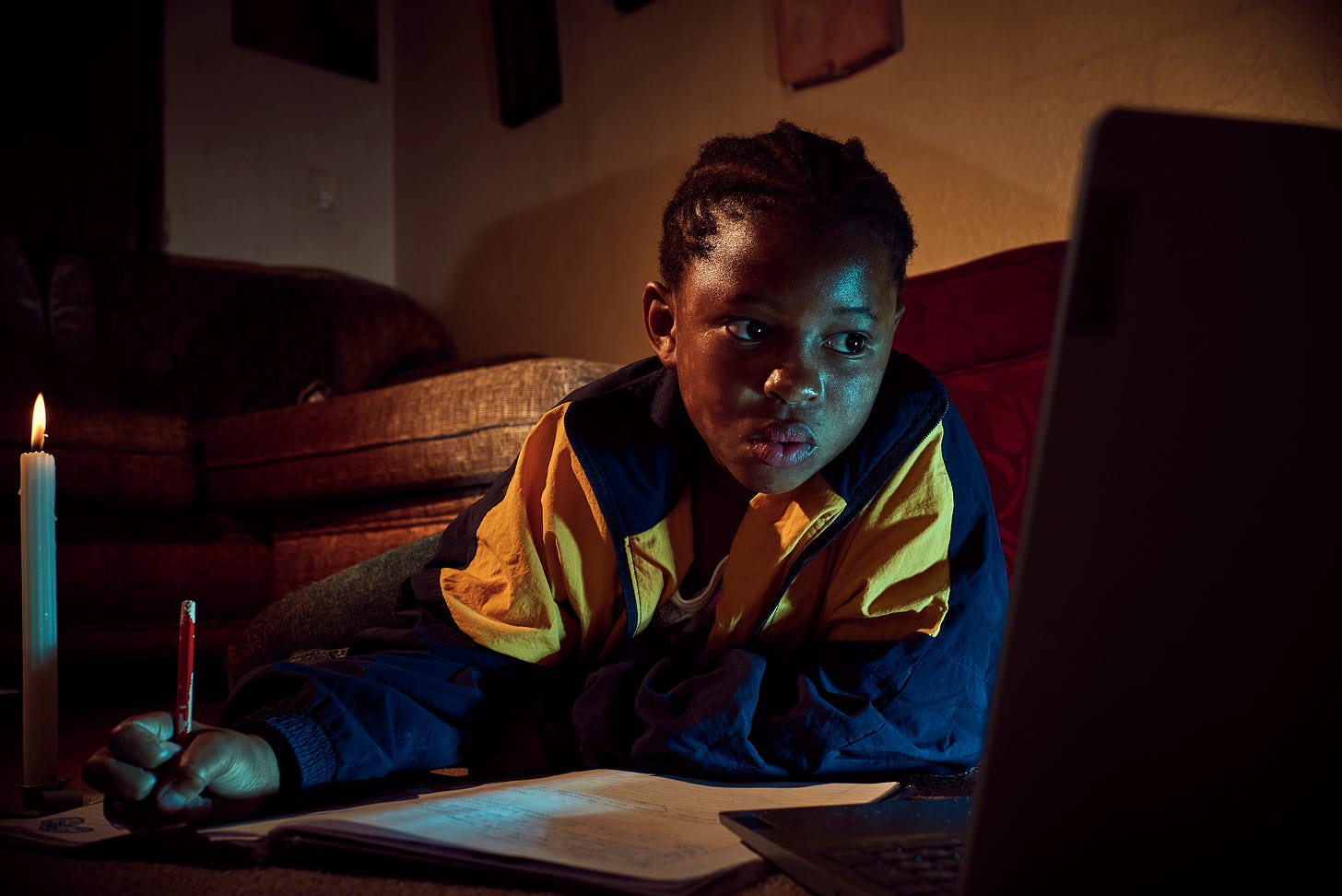

But, in the classrooms of Africa, we’re still far, far away from the utopian vision of every child having a personalised tutor on hand 24/7 – not least because the fundamentals of the education system in resource poor countries changes very slowly. We are, though, seeing a bubbling of innovation – a willingness to try new ideas, and a desire to be part of this wave. AI-for-Education.org was born of a wish to link these worlds, and make sure that children in low-income countries are not left behind, again. We need to ensure that the technology is harnessed for the biggest problem in the world: solving the global learning crisis.

In this article we’ll discuss what’s happened since ChatGPT exploded into the public conscious two years ago; how new tools have, and continue to emerge; but also, how the practical realities of education and international development means that we’ve a lot of work to do to ensure kids don’t get left behind. Some of this is creating products – but, more importantly, it’s about shaping how we as a community help, as well as thinking about how we can learn from other sectors to deliver lasting change.

Market Failure Matters

The painful reality of new technology is that it needs investment to get it right and a viable market to buy it. For education in many countries, that market isn’t there – parents can't afford it, governments are stretched thin, with all budgets consumed by teacher salaries, and implementing partners either can’t buy it (due to rigid procurement processes) or are risk averse and locked into multi-year delivery workplans, meaning innovation is only done at the margins. Even where markets are there, the need to work alongside the education workforce and build on best practices in pedagogy means that just developing software is not enough – people need help to integrate the technology into teaching and learning, which requires a mindset shift.

This market failure means that while the potential is there, we haven’t seen the boom in investment in AI tech for Education we are seeing in other areas, such as FinTech. This is partly due to the huge uncertainties of the technology and the challenges associated with its delivery.

So why does this matter? Well, simply because AI — and generative AI in particular — offers an unrivalled opportunity to dramatically improve how we do things in education, as much in the global south as in the north. AI is amazing at generating new text, sounds and images based on the data it has been trained on. The top models are scoring 80% on teaching exams, i.e. exams teachers would take, based on benchmarks that evaluate their pedagogic ability, not just content ability. As they are run in ‘the cloud’ they can be accessed anywhere there’s a signal (and offline LLM’s mean smaller ones can be used in places where there isn’t). We started with this a few years ago – theTeacher.AI brought support to teachers in rural Sierra Leone – and have seen (and helped) partners build similar support in Kenya and elsewhere.

The Potential Prize

People have spent the last few years thinking how to adapt large language models for different education system, and get their own local content in. Open, high-quality lesson planning tools are now available for free in high-income countries and people are building these around the world. AI means that you can now mark millions of audio clips of students quickly and provide teachers with insights on areas where students are struggling (Wadhwani). You can now take photos of kids handwriting and give back feedback on their misconceptions (SmartPaper); AI can listen to kids' reading, provide instant feedback, correct their pronunciation and reward their progress (Bookbot). It can listen or watch a teacher giving a lesson and provide feedback in the same way that a coach would (TeachFX). And the evidence is promising – with emerging studies, such as Rori, showing an AI chatbot can increase learning outcomes by 0.37 SD – and meta-analysis across HIC finding positive gains. If you want to know more – you can even ask our AI chatbot based on the evidence library we’ve built up.

The potential exists – but how do we turn it into reality? At the AI-for-Education.org initiative (with generous funding from BMFG, Jacobs Foundation and FCDO) we spend a lot of time thinking about this. Usually this question is answered by an appeal to “more personalised learning apps; more lesson plans”, and so on. Looking across the innovators in every country in our community, we don’t think that’s enough. We believe that if we get the AI ecosystem right, the apps will follow.

This brings us to the critical question : “What do we need to do to prepare the ecosystem – the environment – for the flowers to bloom”? This is a bigger challenge, but also a bigger win.

Delivering the Bigger Win

Data is the new gold. As the models predict on what they’ve seen or been trained on, getting them to read the right things is key. We’ve spent the decades since the advent of the PC creating hundreds of millions of words to improve education – if we count up the number of training guides, textbooks, project summaries created round the world by education development initiatives we’d be in the multiples of millions without sweating. All of this content needs to be carefully curated into ‘training data’ and shared with those developing the AI systems to ensure that educators lead the development of tech. But, we need to do that while avoiding the “old model” pitfalls of northern bias.

We need to think beyond innovation labs and hubs and think seriously about systems and how we can shape the market of products and users to integrate AI and EdTech into government classrooms and support the education workforce. Many of the current processes in delivery projects are repetitive and can be co-piloted. AI products can support actors at the system level on the tasks that contribute to the design and delivery of national education.

New tech can get information into the hands of those helping like never before — for example, they can aggregate, review and analyse data to support decision-making, support feedback loops throughout the system, enhance professional development (including through school support officers), and facilitate the creation of content for for policy, planning, curricula and teaching materials. Yet much of the tech to do this is currently built externally, outside these projects.

A good example of what can be done came out of close work with the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education and the Teaching Service Commission in Sierra Leone to solve their problems. This work led to tools such as catchment area planning, for identifying optimal locations for new schools in line with the School Catchment Area Policy; the teacher deployment tool for adding teachers onto payroll based on actual needs, guided by EMIS data; and the SQAO chatbot, which allows school support officers to prepare for school visits and provide better feedback to schools.

Finally, Software as a service works when the software is constantly improved – this means we need to move beyond one-off, projectised system builds, where we hope we can transfer a deliverable to the government to maintain. Unless governments miraculously pivot to being tech companies, they’ll at best maintain, but will never have the space, funding or incentives to push to the next frontier. (This applies to implementers as well as to governments – and to funders, who demand to own the IP of everything, but can’t then make use of it).

Open access can help solve this and should underpin all we do. With an open access approach that seeks to create a stimulating environment, AI can be harnessed to develop products that will address the biggest divide of all : the global learning crisis.

Other resources on AI and education :

List of (other) influential voices and organisations in AI and education.

Multiple Substacks on this topic - search AI and Education.

News

USAID has launched its latest Disability Policy, it’s 27 years since their first one.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) has announced a $100m fund to close the gap in tech education, including a focus on AI.

Thanks to those who have given feedback on Re Education. You can still provide comments - please find a few minutes to do so ; it’s anonymous.

Development

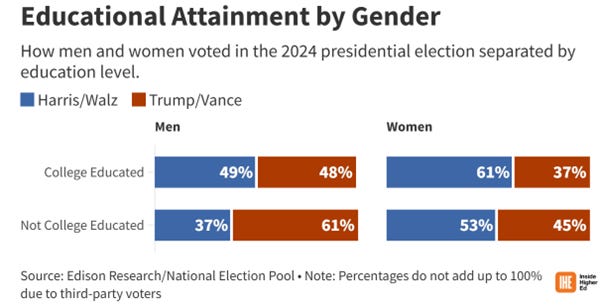

Education matters ! The influence of higher education on voting patterns in the USA is starting to become clear from the November election, an election with global consequences. A recent post by Inside Higher Ed showed that, while ten years ago better educated men and women tended to vote Republican, that has now flipped. In this election non-college educated men voted 2/3 to 1/3 for Trump (caution : based on exit polls).

The respected US commentator, David Brooks, also addresses this as part of a major cover story for The Atlantic examining the way in which an increasingly class divided, in fact, caste divided, education system is contributing to the polarisation of American society. Atlantic Cover Story: David Brooks on the Ivy League - The Atlantic Or if you prefer an easier version see his Youtube interview : “How Ivy League Admissions Broke America:” David Brooks Explains | Amanpour and Company

Voices from the front

As part of the “Global 16 Days Campaign” of activism against violence against women and girls, UNGEI has highlighted Girls’ Congress in the Philippines, part of the Education Shifts Power initiative, created to resource feminist youth-led organisations working on gender equality in and through education.

Luminos Fund are at it again – improving reading and numeracy rates with their accelerated programme in Ethiopia (see issue #8 for an assessment of their work in Liberia). An external evaluation says :

“One month before the end of the 10-month program, students could read 32 correct words per minute (CWPM), an improvement of +28 CWPM over baseline, and their reading comprehension scores increased by 48 percentage points.”

A previous contributor (see Issue #4 on “Multi-grade, Multi-level”), Parthajeet Das, of Central Square Foundation, has put down a challenge, in a blog in South First, asking whether we should introduce a “right to learn” on top of the right to education in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Good idea, or another target to fail ?

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

Is giving cash better than providing free school meals ? A CGD report has some answers from Ghana. (Spoiler alert : depends on the circumstances).

Boys are bigger bullshitters. A study across nine countries finds this to be universally true but with the gender gap smallest in North America. Good to see a clearly titled paper ! Bullshitters: Who Are They and What Do We Know about Their Lives? Cited in an article in the UK’s Guardian newspaper about why men / boys behave badly, see here.

A timely post from Education.org re the importance of phonics, citing a World Bank blog. Reminded me of the fascinating / horrifying podcast “Sold a Story” about how political correctness got the better of technical evidence in the US with disastrous results. It’s not only poor systems ; highly recommended listening.

Interesting blog / paper Unpacking the impact of NGOs on development. Guest post by Sarah Shaukat on the impact of NGOs on social services. Using a “natural experiment” when some NGOs were deregistered in Punjab, Pakistan, the authors find that children, especially girls (disproportionately targeted by NGO education interventions) were less likely to attend an NGO run school, or even a government school.

Intriguing paper on the lack of a link between policy evaluations and changes in spending on the policy area in question. The thread around this link is also helpful. Basically, no correlation between evaluation and spending, even for RCTs. But, timeliness and political connections do show a link.

History Lessons

Professor Angela Little’s book “Development, Education and Learning in Sri Lanka : An International Research Journey” is a great, historical tour of her over 50 years of research and work in that country. It’s free to download here. Click the link below for my book review.

She quotes an amusing example of on-the-hoof policy making :

“A spur of the moment policy decision

… At these functions the secretary had no particular role … except [to] sit there for three hours on the main stage. Therefore, I did not even bother to take my spectacles along … Everything proceeded smoothly until the project minister for education services began speaking. The president’s speech was to follow … Suddenly I saw the president looking back … I quickly got up and went to him. He seemed elated at the largeness of the crowd and their response. He said ‘I want to give free school uniforms to the children from next year. Each one would require at least two sets, isn’t it?’. I was completely stunned, but stammered ‘To all?’. He said ‘yes.’ I had the presence of mind to say ‘but there are 4.2 million children’. He said, ‘in that case we can make it one uniform,’ and continued, ‘Can you work out the costs?’ ‘When?’ I inquired. What he said to this would have killed me if I had a weak heart, ‘Now’ replied the president, ‘I want to announce it in my speech!’ That was President Premadasa. He went on the basis that nothing was impossible and many a public servant was faced with an impossible deadline. This day it seemed to be my turn. I walked back to my seat in a daze … Fortunately one of my accountants who happened to be standing at the back of the stage had with him a calculator … In the end we got the figure of approximately 700 million rupees … I walked quickly up to the president, gave him the figure, but warned him that there could be up to a 20% margin of error. He appeared startled at the cost indicated and said ‘can’t be so much’. The next minute he had to get up to speak, but he was now more cautious. To the vast cheers of the multitude he announced that ‘With effect from next year I will also try my best to give one set of school uniforms free to every child once a year.’ The people cheered so loud and so long the effect was clearly visible on the president’s face, that I knew there was no going back … The die was cast. (M. D. D. Pieris, 2002, pp. 589–91).” Quoted p163.

…and finally

This is so ineffably sad.

Palestinian children were given headphones and asked what they would expect to hear ? They anticipated sounds of war… instead they heard sounds of school. See their reactions.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.