Re Education : Issue #15 - Education : Life and Death

A newsletter about international education development

(If this message does not format properly in your email - please click the “Read in App / View in Browser” above, top right).

Long before my career in international education development I worked in a probation hostel in London. The hostel was a last chance saloon for young offenders facing a custodial sentence. Keeping out of trouble for a year at the hostel would help them avoid prison.

My experiences there sparked in me an interest, and sympathy, for young people who find themselves in the criminal justice system. And I came away with a strong sense that their (usually negative) experiences of education play a crucial role in those journeys to criminality. It also convinced me that most of the money spent on incarceration would be better spent on rehabilitation. [See some character sketches I wrote then].

That theme of rehabilitation features strongly in this years’ Reith Lectures, a British tradition where a notable figure in public life is given a platform by the BBC to talk about a topical issue. This year’s lectures are given by Dr. Gwen Adshead a psychologist who has spent over 30 years working with violent prisoners in the UK : the theme of her lectures is violence and rehabilitation - they are well worth a listen.

One of the questions she poses is why men are disproportionately responsible for violent crime and how much traditionally gendered upbringings have to do with that ? That’s a question anyone engaged in School-Related Gender-Based Violence (SRGBV) will be very familiar with.

That theme of violence and gendered upbringing, and the theme of education as a preventative for crime as well as a means of rehabilitation from crime, also appears prominently in our guest interview this month with Samira Sadeghi, a former lawyer who worked for twelve years with men on death row in California. There, the (negative) experiences of education could have life and death implications.

In our discussion she reflects on the connections between education and the men she met on death row, and how that legal training, and empathy has proved an asset in her current role working to support good governance in English schools.

Schools are not a panacea to all social problems, but schools and teachers are often the sentries in the watchtower - the first to see trouble as it starts to develop. How schools respond to those signals depends on their culture, their leadership, their governance and the values they espouse. The initial responses of teachers and school leaders to children in distress can shape the path of young lives for good and ill ; even life and death.

Andy Brock, January 2025

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

“Through violence you murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate…. Returning violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars.” Martin Luther King Jr.

Interview with Samira Sadeghi

Andy: Sam, you’re an American of Iranian descent who worked with prisoners on death row in California for 12 years before specialising in the governance of English academy trusts…..that’s quite a varied career ! How did it come about ?

Sam: Well, ..both my parents were born in Iran. They studied medicine in Iran, but came to the US for their residencies. I was born in Chicago, and we moved back to Iran when I was four and lived there until I was ten. I learned Farsi and English and attended an American school in Shiraz. We were fortunate to live a comfortable, Westernised life, which wasn't the experience for most Iranians.

Andy: How did you manage to leave after the revolution in 1979 ?

Sam: We left for Germany, pretending to go on holiday, and stayed with friends while sorting out visas. I’m not clear whether my parents already had green cards or used my American passport to secure their entry to the USA. I grew up in Los Angeles and, facing the classic Iranian, parentally influenced choice, of either medicine or law, opted for law. After that I pursued a master's degree in international history at the London School of Economics, focusing on the Suez Canal.

Andy: But, then you returned to law via law school in San Francisco. How did you end up working on death penalty cases ?

Sam: I was passionate about human rights – in fact, I worked for Amnesty International in my year in London – but, I struggled to find work in that field. Death penalty law felt closest, and I secured a position at an agency representing men on death row.

We worked on habeas corpus petitions (alleging unlawful detention), allowing us to reinvestigate cases and uncover new evidence. Often, the trial lawyers hadn't presented a complete picture of the client to the jury. We built up comprehensive social histories, highlighting the impact of multi-generational trauma, poverty, and neglect.

Andy: What role did education play in these social histories?

Sam : Education was critical. Many of my younger clients' lives might have been different if they had a positive experience with a consistent adult figure, either in their family lives or at school. We know from research that just one consistent and reliable relationship with an adult can help vulnerable young people avoid crime – that adult, in a dysfunctional family situation, can often be a teacher at school.

Nowadays, safeguarding practices have improved significantly, so if someone shows up to school with bruises today, or shows signs of neglect, it would be much more likely to trigger an investigation. I would also say most of my clients were neurodivergent, but it’s hard to know whether that phenomenon was caused by trauma or something that was already present in their families.

Overall, my clients’ education experience was important – more for what it was not than for what it was. It wasn't that school was the sole cause of their problems, but rather that it failed to provide the support they needed.

Many of my clients had intellectual disabilities that should have made them ineligible for the death penalty (below an IQ of 80 the death penalty cannot be applied). Part of my job was to try to demonstrate that the initial IQ tests had not been conducted properly and that my clients real IQ was below the threshold for execution. But, there are always borderline cases, like the man who scored 89. Fortunately, the attorney general on that day, a certain Kamala Harris, decided not to pursue the case. (Of the 8 cases Sam worked on over 12 years, none has been executed).

Andy: How did you move from death row to supporting academy trusts in England ?

Sam: My husband is British and, when we moved back, I became a parent governor at my children's school, which led to a governance role at Ark Schools and then to Academies Enterprise Trust (now Lift Schools). My background in the law and legal frameworks, and my experience of sitting on many exclusion panels was definitely an asset. I then became Director of Trust Governance for the Confederation of School Trusts (CST), a body that supports Trust schools through advice, training and advocacy across England.

Andy: Academies now form more than 50% of the schools in England. You are not representing CST in this conversation, but I’m interested in your personal view - is it a good model ? (nb : academies are schools not under Local Authority control, set up as charitable companies responsible directly to the Department for Education).

Sam: When implemented well, with effective governance and shared services, it's highly beneficial for school improvement. However, the structure itself doesn't guarantee success. But, you are much more likely to have better outcomes if you have a governing entity whose sole focus is on one thing : providing education. Collaboration is key, trusts working together with other experts in their sector, other schools, is a much stronger model : single academy trusts (single schools) don't fully embody the trust model. Comparing education trusts to healthcare trusts – no one doubts that a trust which is focused on medicine, and has that healthcare expertise, should be carrying out healthcare, so why does it become a question in education ?

Andy : Is that because there is an alternative model in Education ? The other 50% of schools are supported by County Councils who, previously, were the only bodies with that education expertise in terms of staffing and support.

Sam : Yes, but the support is / was not provided consistently across the sector, and, let’s be honest, County Councils have been massively underfunded – they’ve lost nearly 40% of their budget, which is not their fault, but it means there is no expertise left there.

Andy: You current role is to promote good governance in school Trusts : why is that important to schools ?

Sam: Well, executives and managers are always going to be focused on the day-to-day and the details of problem solving, especially in multi-academy trusts. I think it’s important to have a Board whose role is to keep their eyes on the prize : the strategic direction of the trust, the school outcomes etc. Most countries have some form of school governance, but it differs, for example, in the US some boards are elected and paid – so there’s a different accountability structure there – but it’s still accountability.

Andy: Is the reliance on volunteer governors in trust schools in England unusual?

Sam: Well, while it seems surprising at first, and we do ask a lot of governors of trusts, many countries (e.g. Australia, France, Denmark) utilise volunteer governance systems for schools. The voluntary aspect ensures individuals are motivated by the right reasons – and the volunteers tend to be from that neighbourhood / community which is an important aspect. However, one downside is that it can limit diversity and make it difficult to represent the broader community, because those who volunteer need to have the time and space to contribute. Financial compensation, or paid time off from employment, could broaden the pool of potential governors.

Andy: External inspection is another aspect of school governance – what are your thoughts on Ofsted (the Office for Standards in Education) and the impact of external inspection?

Sam: First of all, you need both internal and external assessment – and external assurance is crucial for good governance. However, challenges arise when you have an accountability and regulatory system which isn’t joined up and that leads to a misalignment of incentives. The 2021 report on Locality Models showed that high performing systems have an alignment of incentives.

The other issue is that Ofsted inspections, with their limited timeframe (a day and a half) and reliance on metrics, risk oversimplification and unintended consequences. Jerry Z Muller’s book The Tyranny of Metrics demonstrates that, as soon as you introduce metrics, you change behaviours : teacher teach to the test, managers try to game formula etc. For example, recently a small number of trusts have been training their senior staff to be Ofsted inspectors and their schools are doing better in inspections – which is perfectly legal, but makes my point about gaming. I believe any evaluation system should prioritise development and collaboration rather than focus on high-stakes judgments. Ofsted should be working with schools, especially when they are not performing well.

Andy: Do you see any broader trends in governance models and accountability systems?

Sam: Well, I think the whole "new public management" approach has had its day. This focus on metrics and targets and incentives…it just doesn’t work. Yet, you have the Secretary of State for Health, Wes Streeting, talking about re-introducing league tables for hospitals : has he not seen what has happened in the education sector ?

Simplistic doesn’t work – we need to be thinking about complexity. Education is complex and can't be reduced to simplistic measures.

Resources

Some links on education and rehabilitation in the global south :

Education a key feature of prison reform in the Dominican Republic. Over 13 years 18,274 people have participated in 472 educational programs.

Rehabilitation is a key plank for Ghana Prisons Service reform.

Distance education for prisoners in Pakistan.

Links on SRGBV

UNGEI Resources on SRGBV :

Girls Education Challenge (GEC) Resources on SRGBV :

Pathfinder in Nigeria : Strengthening the Response to Sexual and Gender Based Violence in Nigeria - Pathfinder International

Organisations supporting the children of incarcerated parents, and their schools, usually with a strong emphasis on ensuring education continuity :

International Coalition of Children with Incarcerated Parents (INCCIP) – supporting the children of prisoners worldwide including India, Uganda and parts of South America.

Children of Prisoners Europe (COPE). They also provide a toolkit for schools to support children with a parent in prison.

Families Outside provide a booklet called Guidance and Resources for Schools in Supporting Children Impacted by Imprisonment.

News

UKFIET held a seminar in November on Responding to Scholasticide in Gaza – see link for details of the seminar and the report and recommendations for action. See also “The mystery is why so many countries are silent on Gaza” by Irish writer Shona Murray.

74 Children were killed in Gaza in the first 7 days of 2025. Barely mentioned in the news.

Some good news from the US despite continued concern about the impact of the Trump administration on USAID. On December 11th in a rare bipartisan initiative, the Reinforcing Education Accountability in Development (READ) Act Reauthorization Act of 2023 will reauthorize the READ Act of 2017 for an additional five years. The legislation calls for a whole of government strategy to improve foundational literacy and numeracy in basic education and requires a yearly report to Congress and the public. See here for an indication of how much lobbying went in to achieving this.

Javed Malik published a moving eulogy to Arif Naveed, a Pakistani social scientist, well-known internationally, who studied education policy design. Naveed argued that education policy design often perpetuates inequalities by overlooking how social dynamics like caste, religion, and political patronage impact opportunities for social mobility.

Development

See this post from Bess Herbert, highlighting a recent UNICEF report (and conference in Bogota), on the shocking statistic that 1.6bn children are “regularly” subjected to violence at home. A clear link to our feature article this month – violence begets violence.

Sal Khan, Khan Academy : Sal Khan: How AI could save (not destroy) education | TED Talk

The Economist has been very active writing about education over the holiday period with several articles, including AI’s potential for good in education, and a left-field, but nonetheless intriguing, piece on whether the Inuit practice of giving their children educational toys may have allowed their survival in Greenland where the Norse people failed. (Good news for the Inuit that it’s unlikely Trump got any educational toys…..)

Euan Wilmshurst has produced a really useful spreadsheeet for educators, showing all the major conferences and meetings about education and development taking place worldwide in 2025. It’s open source, so please add to it.

Voices from the front

The Itinga charity, founded by Acen Kevin (Daniela) has a well-produced video on its activities supporting children with disabilities in Northern Uganda. Daniela posts regularly on LinkedIn. See here also for the first visually impaired news anchor in Uganda, reading the news on the International Day of Persons with Disability.

The last issue featured some largely positive views of the potential of AI to address educational problems in the global south. But, around AI in general there is a lot of the usual frothy optimism that tends to accompany EdTech. This post provides a useful antidote, with a focus on some notable failures, including the World Bank report on Bridge International Academies (now rebranded as NewGlobe).

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

Great piece by Harry Patrinos in The Conversation re the positive personal and social returns from educating girls in Afghanistan (much higher than world averages). Sad to witness the Taliban ideology lead to national self-harm.

A very interesting new study rubbing the shine off one of the most celebrated case studies of education system success in South America – Sobral, Brazil. Lee Crawfurd of CGD summarises what might be going on : overhype, gaming, foot off the gas – or a combination ?

CGD again : a new study reviewing previous studies and adding new systematic reviews, provides considerable credibility to school feeding as an effective programme positively impacting enrolment, attendance and learning. “Do School Meals Boost Education in Low- and Middle-Income Countries? A 15-Year Review” by Amina Mendez Acosta and Biniam Bedasso suggest school feeding is most effective in the poorest countries and for the most disadvantaged groups – but, notes that cost-effectiveness data is still the weakest link.

Education.org says 80% of “research” is unpublished and is trying to broaden the definition of research. See here.

…and finally

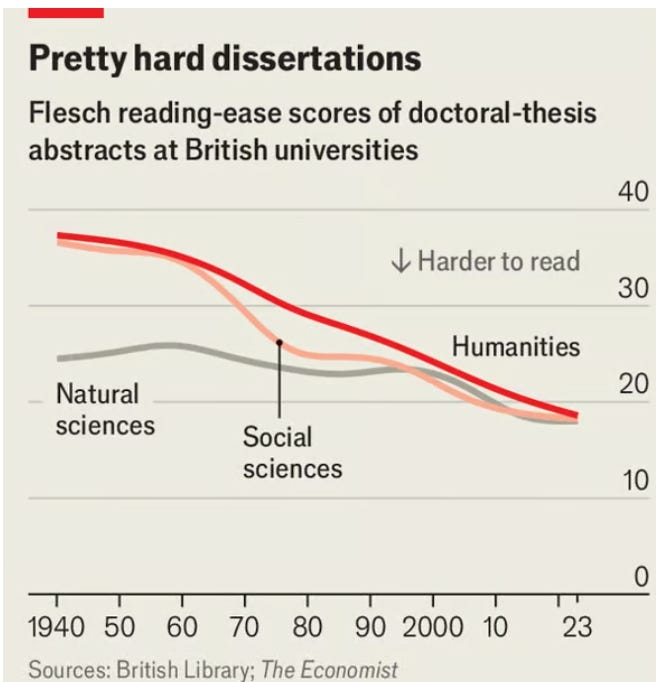

The Economist again – on the increasing impenetrability of academic writing. They analysed over 347,000 PhD abstracts over a 200-year period (!) and rated them for readability on a scale where below 30 indicates it is very difficult for a US secondary school student to understand – results in the chart below.

See also this post by Javed Malik on obscure language in an article about education in the global south (the comments are interesting too). In response, Vicki Collis reminded us that a broken peer review system may be adding to this phenomenon.

Though I am often critical of my academic friends in their thesaurus towers, I do feel this fusillade is so indiscriminating that it risks further legitimising the dumbing down of public discourse we see all around us. There is a balance here between language that is deliberately abstruse, signalling a kind of intellectual onanism, and language that is difficult, uncommon, unfamiliar, but nonetheless conveys, succinctly, theories, concepts, abstract ideas etc. Extending mastery of language and vocabulary should be celebrated and encouraged (with the exception of management speak, we need to draw a line somewhere). As educators we should be promoting the use of language to its fullest extent in order to expand the linguistic and intellectual horizons of learners. And yes, that includes words like liminal and praxis.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.

It's so interesting to see neurodivergence being mentioned in this context. I wonder if the interviewee happen to establish a correlation of neurodivergence with how they were treated in school.

Yes, interesting. I will ask her.