Re Education : Issue #16 - Philanthropy in education : of Logos and Egos

A newsletter about international education development

(If this message does not format properly in your email - please click the “Read in App / View in Browser” above, top right).

According to the International Education Funders Group (IEFG) Spotlight Report on Education Philanthropy in Africa published in 2024, total philanthropic funding to education in Africa tripled between 2019 and 2022, from US$ 290 million to US$ 867 million (OECD 2023). At the same time traditional donors have been reducing aid budgets overall (UK, France, EU, Sweden), and budget to education specifically e.g. FCDO has reduced its education budget by 67% in 4 years.

Add to this picture the shocking evisceration of USAID, and we may be witnessing a change to the aid landscape, including education, more profound than any in the last thirty years. Philanthropies have already become more important in the education sector, and they look set to become even more significant players in the future.

A good moment then to look at how philanthropies are currently performing and what we might expect if they start to play an even more critical role in supporting education in the global south.

The article that follows is a short summary, designed for email. The full article with much more detail can be accessed via the link below.

Andy Brock, February 2025

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

Education Philanthropy

Background

The focus of this article is on large international philanthropic organisations working in education in Africa (87% of philanthropy in Africa is international) : including Mastercard Foundation, Jacobs Foundation, Aga Khan Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Dell, Gates Foundation, Porticus and a few others – organisations who are big enough in terms of funding or influence to make a difference at a country level with their support to education.

Data from OECD and IEFG highlight that education is the second-highest priority for international philanthropies and the top priority for domestic ones.

Mastercard is the largest funder, contributing over a third of all philanthropic education funding in Africa, but it is not even in the top five for basic education (see charts below).

Why Philanthropy ?

Or, to put it another way, if governments could support and fund education systems fully would we need philanthropic organisations ? That question seems almost redundant in the context set out above – good, bad or indifferent, philanthropy is here to stay.

Nonetheless, philosophically, it’s worth asking why we need philanthropic organisations in the education space – if only to better understand what unique contribution they can bring and what motivates them.

In responding positively, most respondents claim that the unique contributions of philanthropic organisations are that they can be : strategic, risk-taking, and longer-term focused than traditional donors. Those claims warrant scrutiny.

This analysis examines their impact across six dimensions:

Strategic focus

Alignment with government policies

Risk-taking capability

Collaboration and coordination

Sustainability

Accountability

1. Are Philanthropic Organisations Working Strategically?

The trend among large philanthropies is toward greater strategic focus. Geographically, there is a trend for a smaller footprint : e.g. the Jacobs Foundation has concentrated its focus from 35 countries to just four ; the LEGO Foundation is now focusing on less than ten countries ; Porticus operates in only eight countries, and even Mastercard Foundation who support 37 countries are believed to be reviewing their spread.

At the same time, some countries get a disproportionate level of support due to historical ties or personal connections, a trend insiders call the "Kenya Effect." If all the impact claims about Kenya were true, it would be rivalling Singapore in education outcomes by now.

Thematically, philanthropies are increasingly prioritising foundational learning, (including TaRL and structured pedagogy), and early childhood development. The Gates Foundation, for example, is highly focused on foundational learning and leveraging influence with major donors like the World Bank and UNICEF.

Perhaps the biggest change has been towards prioritising education system building and system change as the essential space in which larger philanthropies can make the most sustainable impact, and where governments generally see the greatest long-term benefit. In this they have been in step with similar changes of focus from traditional donors.

Nonetheless, despite improvements in strategic focus, the overwhelming impression of the sector is one of fragmentation. Many small and medium-sized philanthropic organisations, though doing excellent work, operate in silos, leading to inefficiencies and duplication. Greater efforts at collaboration – pooled funding, even mergers – should be driving the sector, aided by well-established networks like IEFG.

2. Are Philanthropies Aligned with National Government Policies?

Most philanthropies operate with minimal in-country staff, relying on local partners and grantees rather than working directly with governments. While this allows flexibility, it can also lead to a disconnect from national education priorities.

Their boards and senior management teams are largely US / Europe based and while there are trends towards placing key staff in country or regionally, progress is slow. Although delivery is primarily through indigenous civil society and NGOs, they are not always best placed for working with government on systems level change. Organisations like T-Tel in Ghana, supported by Mastercard Foundation to transition from a project team to a local delivery partner, show some promise.

While philanthropies contribute valuable resources, their independence can create tensions with government agendas. The challenge lies in developing constructive relationships directly with government rather than through proxy organisations, where philanthropies can act as "critical friends" rather than conditional funders.

3. Are Philanthropies Taking Risks?

Despite a reputation for innovation, many philanthropic organisations are risk-averse, constrained by cautious boards. Large foundations, often controlled by industry leaders or families, prioritise financial prudence over bold experimentation. Sometimes too, risk is in lack of uptake rather than failure.

However, some organisations do embrace risk, albeit hesitantly. An area like AI in education needs risk-taking organisations to experiment and drive good use cases. With some exceptions, philanthropic organisations have not yet risen to this challenge.

Political risk is particularly challenging for philanthropic organisations. Unlike bilateral donors, philanthropies have limited leverage with governments, making it harder to drive systemic change. Collaborative approaches, such as the “Statement by Philanthropic Actors Supporting Education” at the Transforming Education Summit (TES) in New York in 2022 is one way to signal a more coordinated approach to political risk.

4. Are Philanthropies Collaborative and Coordinated?

The sector is probably more collaborative than the traditional aid sector, though it lacks the latter’s coordination mechanisms. Many philanthropies operate independently, with their own thematic and geographic priorities. Partnerships are more often focused on securing additional funding rather than integrating efforts.

Some good coordination exists ; organisations like Aga Khan Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, Jacobs Foundation, and Gates Foundation co-finance initiatives. But the fragmentation of the sector means higher transaction costs for government and poorer coordination.

In 2005 the Paris Declaration sought to streamline interactions with governments by aligning processes and enhancing collaboration. It feels like these lessons are having to be learned all over again.

Indigenous philanthropic organisations in Africa, India, and Latin America offer potential collaboration opportunities for international philanthropies – and networks like IEFG are well placed to assist with information sharing and joint working (for an excellent summary of the opportunities and challenges see Kat Pattillo of Edwell in this article).

5. Are Philanthropies Focused on Sustainable Change?

Sustainability in philanthropy is often viewed through the lens of securing continued funding rather than embedding initiatives within government systems. Many hope government will institutionalise successful programs, but to be successful this requires intentional and active planning at design stage.

Philanthropic funding, while seemingly miniscule in the context of any education system, needs to be compared to the less than 5% of funding available to most ministries of education after teacher salaries and materials have been covered. From that perspective philanthropic funding can actually be significant in promoting new initiatives or facilitating reform. The potential to "crowd out" or substitute for government investment also needs to be recognised.

A broader sustainability challenge is how to shift strategy-setting and decision-making power to the local level. As one respondent commented : “There is much talk and little action – no one wants to voluntarily give up power.”

6. Are Philanthropies Accountable?

Philanthropies are primarily accountable to their boards rather than to democratic institutions (unless government co-funding is involved). Unlike government aid agencies subject to parliamentary or Congressional scrutiny, philanthropic organisations operate with limited external oversight, though often very strict financial scrutiny. But, the differences are not as significant as they may appear.

Guarding against reputational risks serves as a form of accountability for those with high profiles. Philanthropies like LEGO Foundation, and Mastercard Foundation who have connected commercial arms are wary of scandals that could damage their brands. Voluntary transparency of data, strategy, spend and of decision-making may be something the “industry” needs to adopt to ensure continued public credibility.

Internal accountability varies. Some foundations lack rigorous financial oversight, while others impose strict financial controls but minimal technical supervision. Strengthening both financial and programmatic accountability remains an area for improvement.

Conclusion

As philanthropic organisations become more important within the education development sector in the global south, there needs to be a better understanding of their comparative advantages, greater transparency on their motivations and operations and greater scrutiny of their role to facilitate indigenous philanthropy and locally led education organisations.

The emasculation, if not complete defenestration, of the world’s largest bilateral donor, to be followed in short order by significant financial pressures on multilateral agencies dependent on US money, is already leading to a crisis where philanthropy is being looked to as a “saviour”. They will not be that, except in some very specific cases (and may, in fact, also be targeted by the Trump administration).

But, outside of the US mayhem, they have the unique potential to be part of a positive solution, a new paradigm for development cooperation that emerges from this shock. To fulfil that, philanthropies will need to be much more strategic, more collaborative with each other and local actors, and more willing to be led by government. They will need to leave their egos and logos at the door.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” (Falsely attributed to) Edmund Burke

News

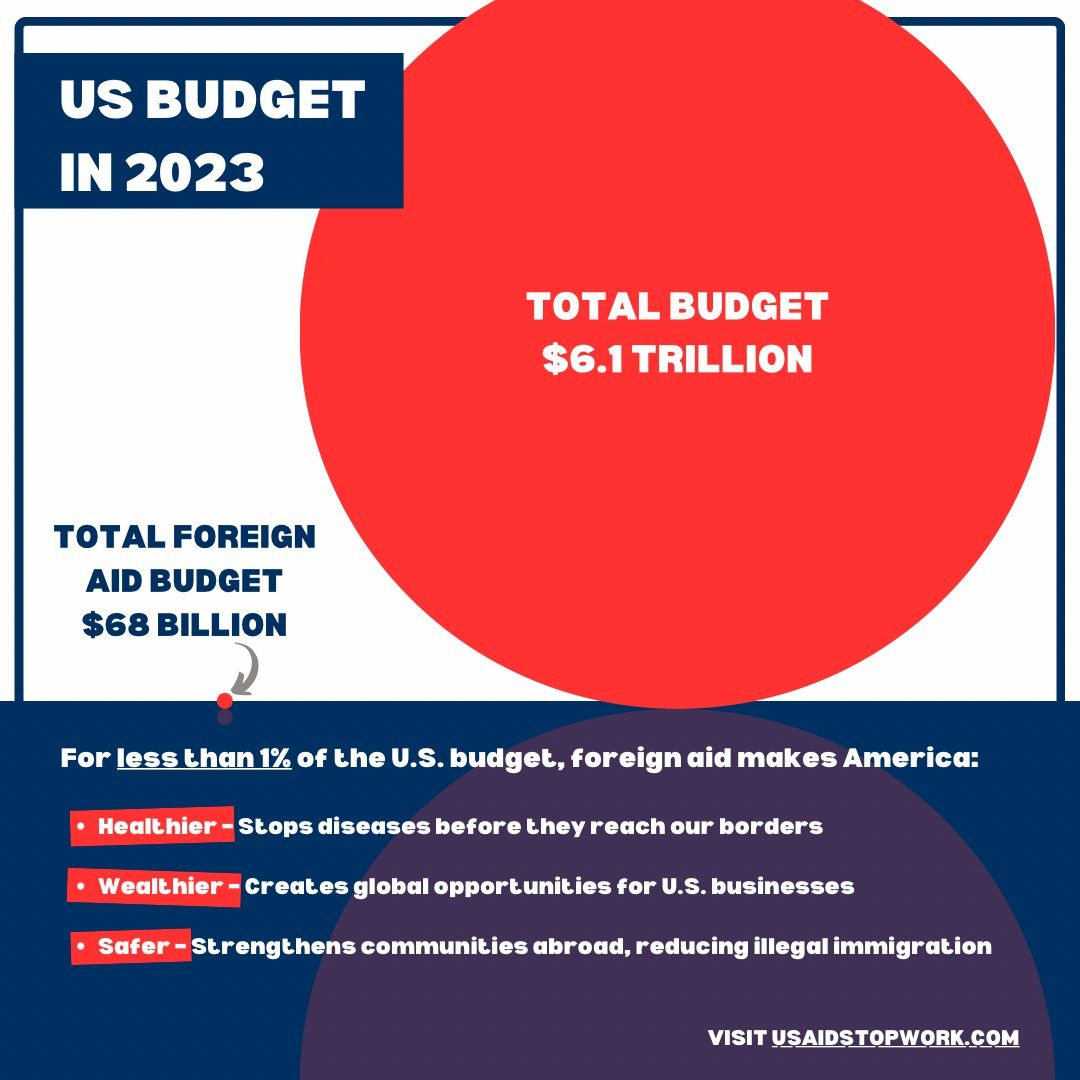

The shocking news coming out of USAID – worsening every day - has stunned the whole development sector. I can’t add much to what others, far more qualified and eloquent than I, have said. I have provided links to the best articles I have read, below. I make only two comments :

1/ The ramifications of this act of deliberate self-harm seems designed to cause maximum political pain with no care at all for the cruelty and real pain inflicted on the most vulnerable. It will have a damaging impact far beyond that caused by Boris Johnson’s puerile destruction of DFID or the Australian and Canadians’ dismantling of Ausaid/CIDA. The only possible responses must be resistance (where possible), mitigation (lessen impact) and preparation (readiness for when times change).

2/ In that latter space – preparation - the themes I wrote about in Issue #11 on Broken Aid, seem more pertinent now than ever. There is an opportunity in this adversity to prepare for a better, less dependent, growth and public-goods oriented model of international support ; it seems distant, but will come.

Some countries will fare better than others. But doing nothing or hoping to reconstruct what existed before Trump some time in the future are not good options. (Ken Opalo)

Among the thousands of words written - this image seemed one of the most effective messages.

First link - for those looking for work, Nora Marketos publishes a regular list of philanthropic job opportunities here.

Ken Opalo, a very thoughtful commentator : On American aid cuts/disruptions - by Ken Opalo

LeAnna Marr was until recently Deputy Assistant Administrator for Education in USAID : Post | Feed | LinkedIn

For those who prefer watching / listening, Samantha Power former USAID Administrator spoke eloquently on Stephen Colbert and Andrew Natsios, also former Administrator, on CNN.

Eric Olander applies a geopolitical lens to the fall-out : Africa, China, and Trump’s World-Spanning Gamble on Foreign Assistance

Well-known educator, Prachi Srivastava puts the cuts in the context of global aid spending on education

Uhuru Kenyatta says it’s not a big deal for Kenya : “stop crying” about it.

Worrying post from Essi Lindstedt on comments about the self-censorship dilemmas facing those still trying to get funding from a US government allergic to words like “gender”, “feminism”, “diversity” etc.

With impeccably bad timing the Swiss Government announced cuts to its aid programmes. GPE has asked them to reconsider.

His Highness, Prince Karim Al-Hussaini, Aga Khan IV, died February 4th 2025. His obituary, from the Aga Khan Foundation, here. The new Aga Khan, Prince Rahim Aga Khan V, made his first address highlighting the continued importance of AKF’s support to education.

The United Kingdom Forum for International Education and Training (UKFIET) has announced the call for abstracts for the Oxford Conference, the largest gathering in the UK of academics, NGOs, private sector and donors, working on development education, held every two years in Oxford. Details here.

Development

A post from Jessica Oddy-Atuona struck a chord with many (nearly 1,000 likes and 70 comments) in the NGO sector. Her pot-shot at the fad for innovation, instead of finding what works locally and doing more of it, could be applied across the whole development sector.

This article in the Indian Express, reflecting on the significant and positive results for reading and numeracy, from the ASER 2024 Survey, is worth reading. A good news story.

UNICEF has published a report highlighting that 242 million students – from pre-primary to upper secondary education – have experienced school disruptions due to climate events in 2024.

Nigeria considers combining secondary education into basic education, changing from a 6-3-3-4 to a 12-4 system. Oyewole Sarumi of EduGist considers the pros and cons.

Voices from the front

A sobering assessment from ActionAid on what the ceasefire in Gaza means for children’s education. Not a return to normal in any way.

A depressing read from Arab News on how war is affecting the world’s children.

In better news - this 3m video from Svitlo School shows good people doing good work as the war continues in Ukraine, and how to help out.

Jakarta, capital to a nation of 284m, and with a population of 11.5m, has very few special schools and none in north Jakarta. Governor-elect Pramono Anung Wibowo plans to change that says the Jakarta Post.

The Learning Crisis in the Philippines : children are 4-5 years behind expected levels reports a Congressional Commission.

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

The Global Status of Teachers Report, 2024 has been published by Education International. This post, from Margo O’Sullivan of Power Teachers Africa, gives a commentary and links to a tl;dr summary from Euan Wilmshurst as well - two for the price of one !

Maria Paradies has a new paper called : ““I do not want to stop teaching”: The impact of conflict and displacement on teachers in southern Mosul”. It’s part of a volume of 23 essays in UNESCO Prospects: "Towards 2030 and beyond: Challenges and opportunities for education transformation” edited by Simona Popa.

A very good new report called “How do structured pedagogy programmes affect reading instruction in African early grade classrooms?” by Ursula Hoadley (funded by USAID).

…interventions like structured pedagogy programmes risk being just new forms of ineffective foreign power like the erstwhile learner-centred pedagogies of the last 30 years.

Hoadley critiques not just the what of structured pedagogy approaches, but the how and finds significant deficiencies. Without that how being addressed investments will be wasted.

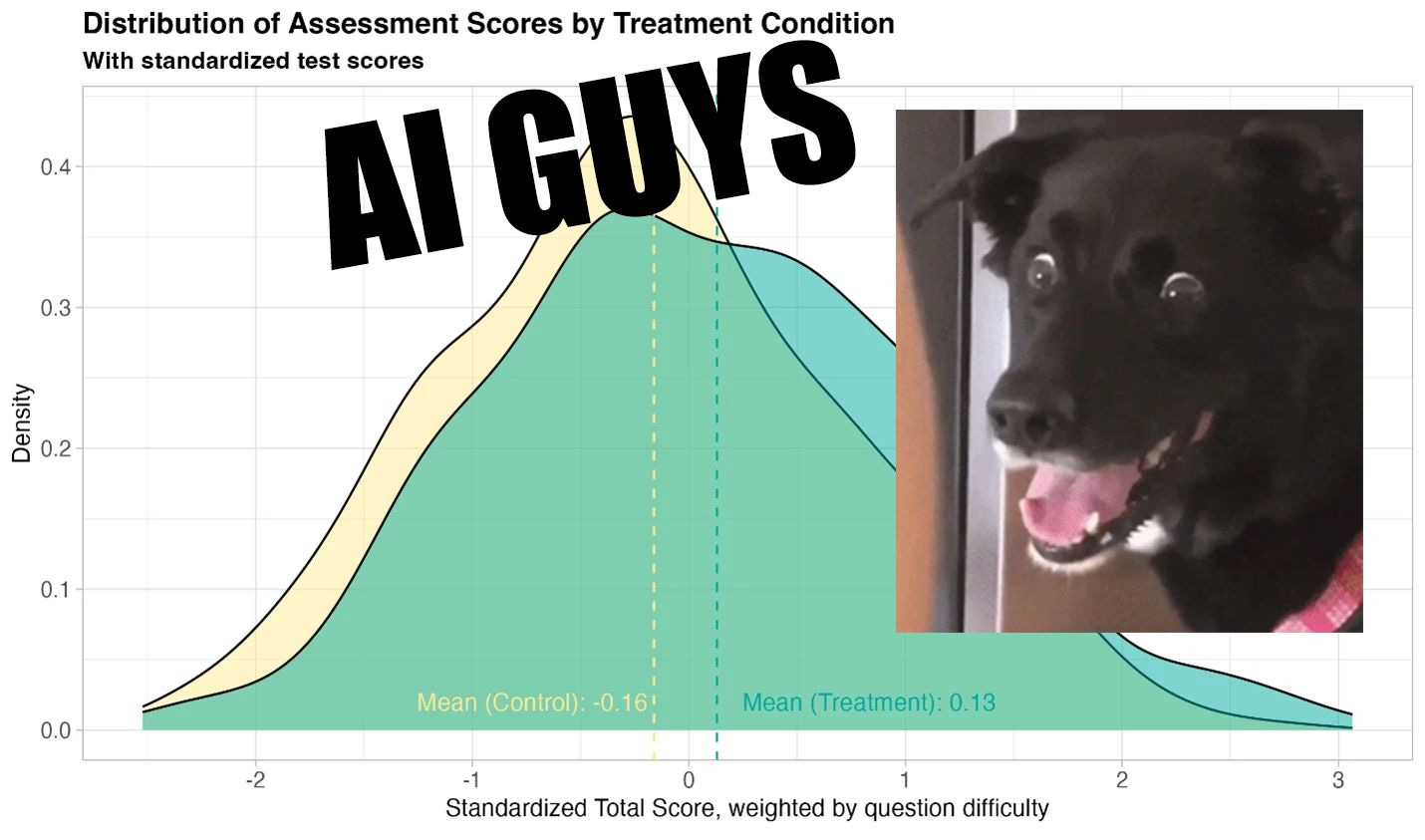

Quite a lot of noise about an AI experiment in Nigeria which made some grand claims about the ability of AI to accelerate learning. The deflators quickly jumped in to point out the potential methodological flaws, assumptions and opaque wording - this is the best example I saw. Perhaps the AI was hallucinating ?

…and finally

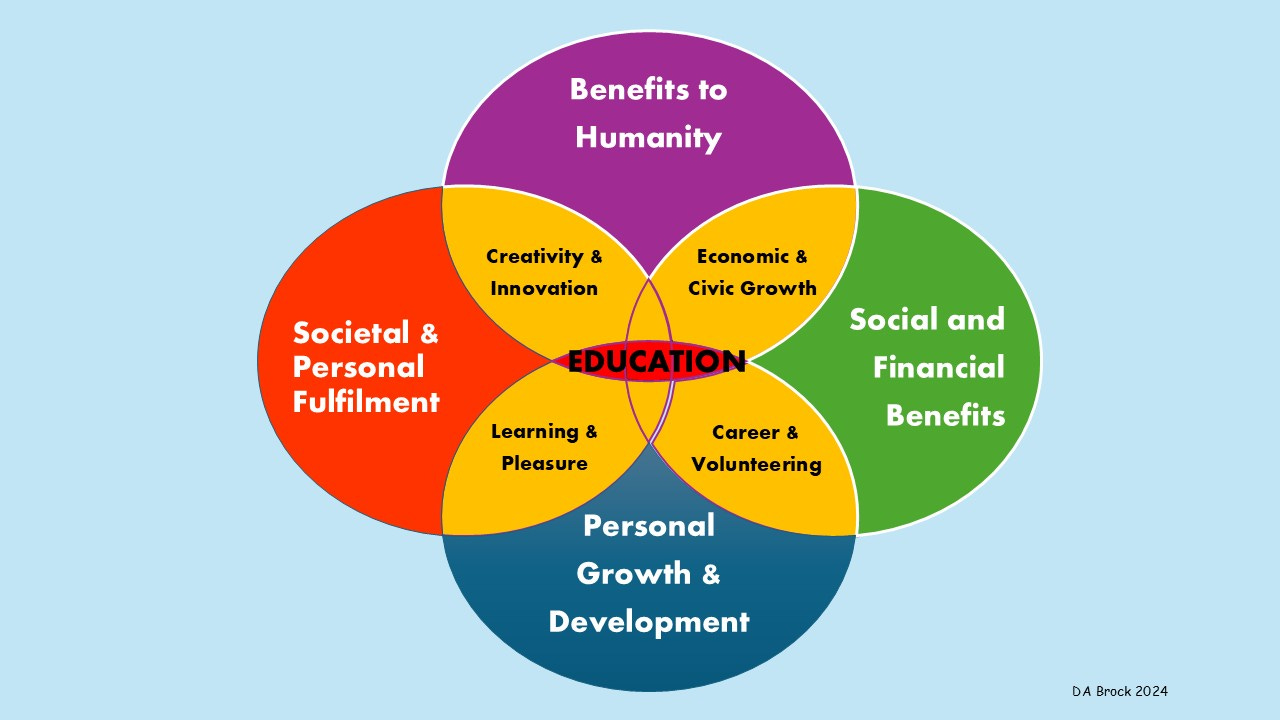

Preaching to the converted…a reminder of why Education underpins everything in our personal, social and public lives.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.