Multi-grade, Multi-level : the curse of the helping hand

Should teachers have to cope with multiple ages, multiple learning levels and multiple demands in classrooms which are resource-poor ? When they have no choice, what can educational leaders, planners and policy makers do to support them ?

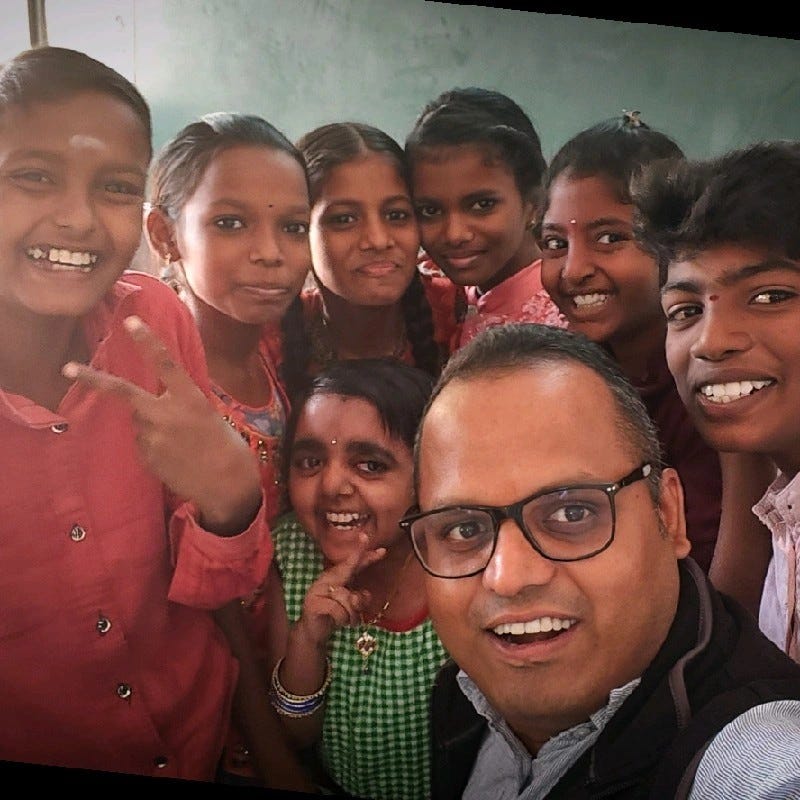

This month’s guest post on Multi-grade Multi-level classrooms (MGML) by Parthajeet Das, Director of the Central Square Foundation in India, writing in a personal capacity, provides an engaging, thoughtful and pragmatic assessment of the realities. The issue of multi-grade, multi-level classrooms is not unique to India, but it may just be the largest education system in the world dealing with it. (Of course, multigrade, resourced well, can be a boon - especially to remote communities).

Das identifies the pressures that have created MGML, the load it places on teachers and the impact on children who are getting a raw deal. He puts forward a well-grounded, five-point plan to support learners and teachers and mitigate some of the negative aspects of MGML.

But, why do some countries have a MGML issue and others don’t ? One part of that answer is the curse of “the helping hand strikes again” i.e. education policy decisions which have not been field tested and lead to unintended negative consequences. In Das’s paper he cites three at least : the requirement to have a school within a kilometre of a habitation ; the requirement to have one teacher for every 30 children ; and a no repetition policy. All of these, individually, are fine aspirations, no doubt designed by good people with good intentions – but, collectively their impact has led to MGML.

A few years ago I wrote about the Brown vs Board of Education ruling in the US in 1954 which struck down desegregation of schools. It was seen as a critical step in the Civil Rights movement : who could be against that ? But, the unintended consequence of this ruling was that almost half of all African American teachers lost their jobs as schools consolidated and white teachers won the competition for fewer teaching posts.

Das has some pragmatic solutions to the problems facing teachers in MGML settings, and not just in India. Those need to be taken seriously to mitigate the harm being caused to children’s learning ; that’s the immediate need.

But, longer term, effort needs to be put into correcting unintended policy consequences that lead to poor learning experiences for children. All political decisions are choices, and not every outcome can be anticipated, which is why regular reflection, review and adjustment are essential.

If you have experience of MGML and insights to share, or examples of other unintended policy impacts, or have comments on the perspectives presented in this paper, please start, or contribute to, a discussion in the chat.

Andy Brock, February 2024

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

Guest Post

Multi-Grade Multi-Level (MGML) Classrooms in India: The problem & approaches : Parthajeet Das, Director, Central Square Foundation, India

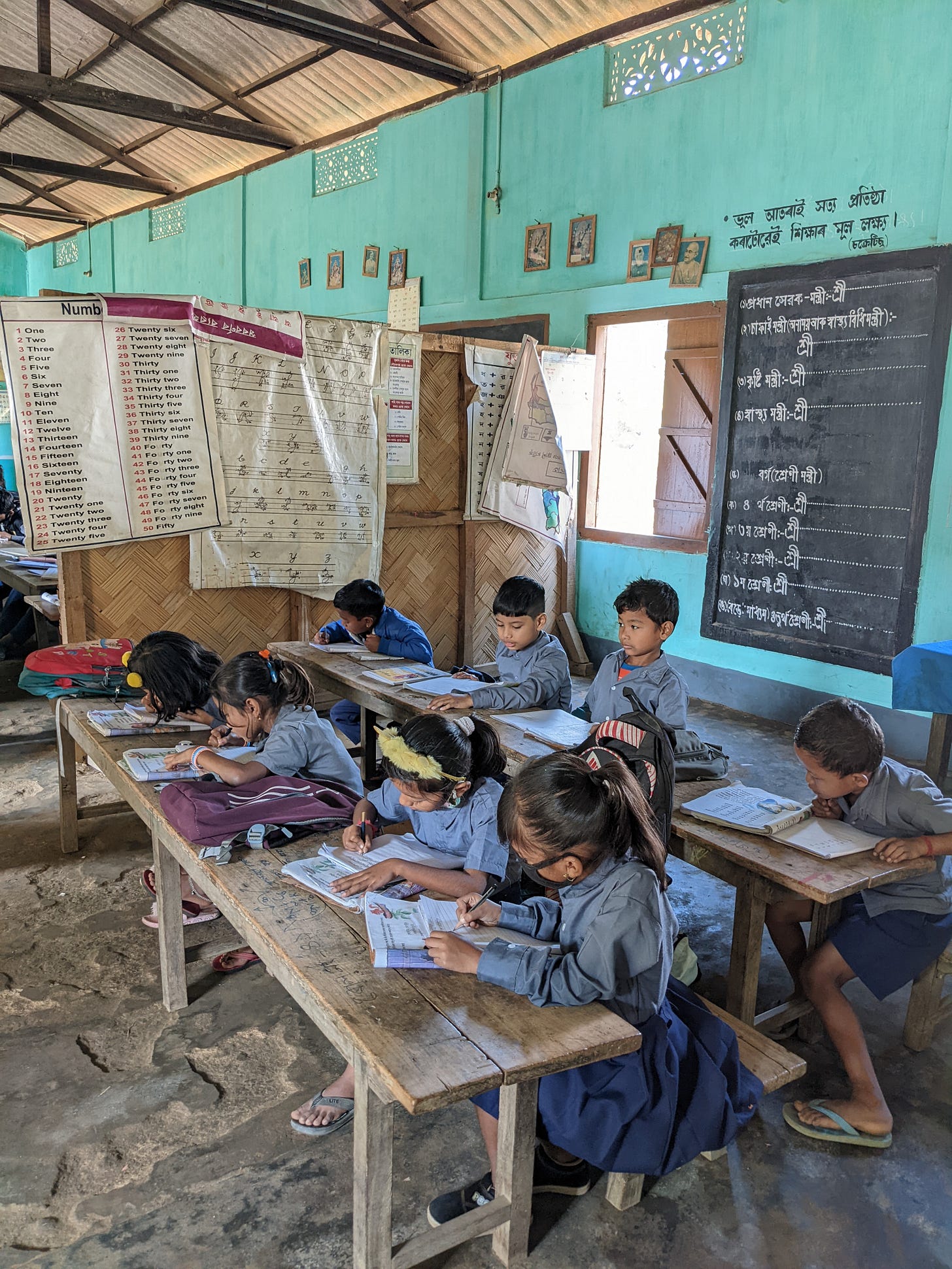

MGML classrooms are a sad reality of government primary schools across many states of India. Essentially, what it means is that we do not have enough teachers or classrooms, or both, and hence teachers end up teaching two, or more than two grades together! Take a moment to picture this for yourself: children of different age-groups, different grades, sitting together in one classroom and being taught by one teacher at the same time. For a large majority of children enrolled in primary schools, this is a reality not just for one period or one day, but for every single day at school.

You might wonder how and why? After all, we seem to have a healthy Pupil Teacher Ratio (PTR) in India. As per the latest Unified District Information System for Education (U-DISE) reports the national level average PTR is 28:1 with a large majority of states having a teacher for 11 to 30 children. As with most averages, these figures hide more than they reveal. Let’s unpack.

The norms for Right to Education (RTE) and state governments allow a teacher post for every 30 students for primary grades (I-V) and for every 35 students for upper primary (VI-VIII) and not grade-wise. Together with the norms of RTE to set-up primary schools within 1 km of every habitation and continuously decreasing enrolment in government schools, we have ended up in a situation where, in more than 30% of the 1 million government schools, the total enrolment in all five grades of the primary schools would be around 50-60 students.

To compound matters an increasing number of private schools (which in many parts of India are confusingly called ‘public’ schools) is further depressing enrolment in government schools. While the number of private schools (22.5%) is significantly less than the number of government schools, they cater to a larger percentage of students (33.3%). The average government school has about 140 students compared to 263 in a private school.

So, most schools will have two or three teachers for all the five grades. In addition, in many schools the number of functional classrooms would be limited to two or three classrooms, again for all five grades. The result, multi-grade (MG) classrooms.

What about multi-level (ML) then? Well, understandably, most classrooms have children at different levels due to differences in the socio-economic background of parents, parental engagement in the child’s education etc. But, another RTE norm, the no detention policy, is greatly responsible for accentuating this. This norm prevents grade repetition, so we have a situation where a teacher teaching in a Grade 5 classroom may have a few children who have grade 2 level abilities and many who are at Grade 3 or 4 level abilities and very few would be actually at age and grade appropriate level i.e. Grade 5 !

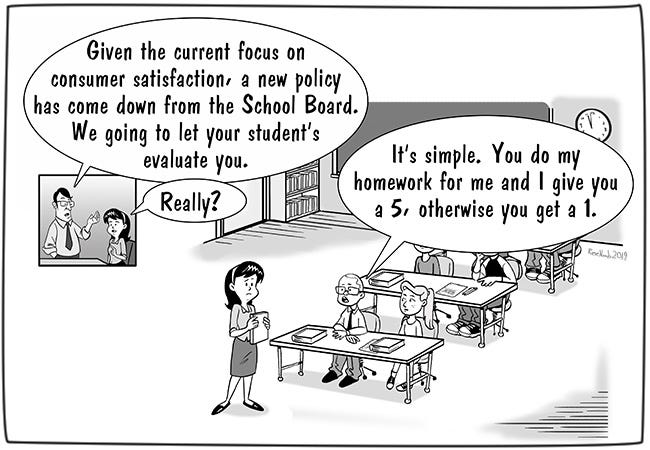

Put these two phenomena together, and we have MGML. While this post is not intended to be a critique of the Right to Education Act, 2009, one can not help but wonder if the ‘solutions of yesterday have created the problems of today’.

Today, MGML is seen as a black bullet (or whatever is the antonym of a silver bullet !) for any serious education reform in the country. Any well-meaning and intelligent-sounding person can use this to ground any advice or planning related to primary school education. "We like all that you are saying about foundational learning, competency-based education, assessments, balanced literacy etc. but we have a large majority of MGML classrooms. The teacher guides and lesson plans are useful in theory & design but how do our teachers use them when they are teaching 2-3 grades simultaneously ?!" This is unfortunately the situation across most states in India, with anywhere between 50-80% of primary schools having a MGML situation.

How does this situation manifest itself in schools? No, you do not see overcrowded classes. In fact, you see classrooms of roughly 20-30 children of different age-groups sitting together and having different textbooks, workbooks open. They are often grouped together as per their grades and while the teacher engages with one section of the children the others are either seemingly engaged in some activity given to them, or playing among themselves, or worse, passively listening to the curriculum of a higher or lower grade being transacted to a bunch of kids sitting right next to them.

In many schools with acute shortage of classrooms, I have seen the school use a thin curtain or a bookshelf to separate two parts of one room and two different teachers teaching two different sets of children. In a few classrooms, they make children of one grade sit facing one direction being taught by one teacher and children of another grade sit facing the opposite direction being taught by another !

What's the way out of all this? Isn’t it straightforward - appoint one teacher per grade and/or build one classroom per grade. Any of these initiatives separately, or together, will have a significant demand on the state education budget and so is unlikely given the backdrop of dwindling enrolment in government schools.

Many states have tried alternative administrative approaches such as rationalisation or merging of two or more smaller schools of a region into a school complex, so that they have a combined larger pool of teachers. But, these measures are very hard to pull off politically (resistance from teacher unions) and socially (community resistance). Some believe that there can be no proper pedagogy that can address MGML and, moreover, that it’s unfair to the children from a right’s perspective. Many others jokingly remark that the first Nobel Prize for Education should go to a better pedagogy for MGML.

My take is that we have to look at some pragmatic approaches, however inefficient they may seem, as a large number of kids are in schools not learning the basics. It’s a huge opportunity cost to them and a risk to society.

I will keep it simple and try to share five broad steps that can be considered - Acknowledge, Assess, Slow it Down, Teach well & Support. Let’s dive in.

Without reflection, we go blindly on our way, creating more unintended consequences, and failing to achieve anything useful.

Margaret J. Wheatley

News

Some snippets of recent news / events that seem worth sharing.

A heartbreaking video on the number of children killed in Gaza and Israel - from Led By Donkeys.

For those worried about the gaping chasm that is the digital divide between richer and poorer countries – perhaps there is hope ? A recent study reported in The Guardian finds that children aged 10-12 learn better with real books and real paper !

Some very interesting and useful data, in a format that’s very user friendly, from ONE.org on development assistance. This is drawn from OECD DAC reports. On Education as a sector, aid flows have been rising, but stayed constant in the last year at about $11.8bn. But this masks some shocking variations, including the UK - from a high of $1.36bn to $564m in 2022. Given Finland’s reputation at the top of the international education league tables it’s surprising to see they have dropped from $134m to $90m in 2022. Just as surprising is the share of aid USAID gives to education dropping from 5.6% of the aid budget in 2018 to only 2.9% in 2022.

Voices from the front

PEAS, the educational charity, released impressive results from their schools in Zambia. 72% of Grade 9 students obtained certificates, compared to 53-62% across the provinces where PEAS operates. They credit this to enhanced leadership support, provision of catch-up services in schools and a partnership with Costa to provide bicycles to marginalised day students.

In a serendipitous connection, reports Dave Evans, a programme in Ghana that encouraged “…school principals to act as leaders to improve classroom instruction ... boosted student performance by 30% in one academic year with persistent achievement effects two years later."

Two personal reflections from staff at the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Pakistan on a Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) funded programme called TEACH that supported 35,000 out-of-school girls. Interestingly, both cite Girls Clubs as being instrumental in raising awareness, empowering girls and creating connections – and in both cases these continued after project funding. I’ve seen similar successful initiatives in Leh Wi Lan in Sierra Leone where Girls’ and Boys’ clubs have had a real impact on reducing violence against women and girls both in, and on the way to and from, schools.

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

A new paper from the prodigious publishing phenomenon that is Lee Crawfurd of CGDEV (if you don’t follow him you should) : “Feasibility First : Expanding access before fixing learning”. I missed this in November when it was released, but it’s a provocative paper well worth reading. Having recently written a piece (see Issue #1) lamenting the lack of commitment to address the Learning Crisis, I was interested to see if this paper would make me challenge my own position. Crawfurd contends that from the perspective of politics (ease of action) and the demonstrable economic returns to secondary education, expanding this sub-sector could be a more cost-effective strategy than trying to improve foundational learning quality.

But, aside from the narrow criteria of judging these choices by economic returns and cost-effective investment alone, he doesn’t seem to address the rather obvious and yet fundamental objection that, for secondary education to expand, you need literate and numerate primary graduates – unless you view the whole education system as a giant babysitting operation. What do you think ? Leave a comment below. Agree or disagree, papers like this are useful to make us check our thinking.

An interesting post by Tanya Guyatt highlighted research on an experimental remedial support programme to address learning loss in El Salvador. Even small amounts of targeted support (by text and phone) showed significant improvements. Interestingly, a parallel investigation to see if such support reduced anxiety showed no / inconclusive impact.

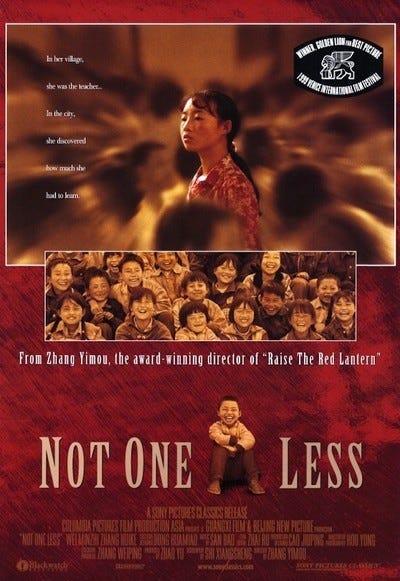

Movie News

Thanks to everyone who joined in the call to recommend movies about education in the global south. I have put the suggestions (mostly made on LinkedIn) in the chat, so they are all in one place. There’s still plenty of time for nominations ! Some excellent suggestions already and most of them are available on streaming or Youtube.

Fun Stuff

Succession, my absolute favourite TV drama, on suing Greenpeace. Watch out SCF !

Kids at school need a rest don’t they ? Looking after mind, body and soul.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.