Re Education : Issue #7 - Is it time for the Education Oscars ?

A newsletter about international education development

Introduction

(If this message does not format properly in your email - please click the “Read in App” above, top right. Clicking any of the video clips will take you to the app to view).

This month’s newsletter format is a little different. The News and Development sections are after the main post and are shorter to allow enough space for the main feature. Get your popcorn and drink, your box of tissues, put your feet up, and enjoy !

Andy Brock, May 2024

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

Emotion is the chief source of all becoming-conscious. There can be no transforming of darkness into light, of apathy into movement, without emotion. Carl Jung

LET’S MAKE A DRAMA OUT OF A CRISIS

Just after Christmas a political storm erupted in the UK over a TV programme called “Mr Bates vs the Post Office”, which dramatised a truly shocking miscarriage of justice. Within days, the overwhelming public reaction to the programme led to proposals for a parliamentary bill to exonerate the thousands of postmasters and postmistresses who the Post Office had wrongly accused of fraud.

What was interesting was that the facts of this miscarriage of justice had been well-known in political and journalistic circles for nearly ten years. There had been numerous articles and documentaries in the mainstream media and a public enquiry had even been established by parliament in 2020.

Many commentators were openly puzzled – why did a TV drama create the reaction it did when many well-written journalistic articles, questions in parliament and a public enquiry did not?

The difference was emotion. The TV drama exposed the emotional facts of the story where formerly only the narrative facts were visible.

Drama is much more effective at generating emotional reactions than words on a page, or even the spoken word. Drama can place you in the shoes of those who suffer, can make you empathise with their suffering. Those individual responses became a powerful collective response through the amplification of mainstream and social media.

Is there something to learn here ?

Can the Education sector learn something from this example of how an injustice was catapulted to national recognition through a TV drama? How might “drama” be used to popularise support for education, or be used to push for the reform of certain practices in education ?

There are many education injustices at both national and global levels: the Learning Crisis that is condemning a generation of children in the global south; unequal access to education for disadvantaged groups – the geographically remote, those with disabilities, minorities; the digital divide as urban, richer groups accelerate advantage; continued discrimination against girls e.g. Afghanistan etc.

So, could organisations who aspire to address inequalities in education provision in the global south – such as governments, donors, NGOs and contractors – invest more in using drama and emotion to enhance understanding and empathy for educational injustices?

Bringing drama to the Education sector

By drama I am thinking here of any form of movie/TV presentation that fictionalises some or all of an educational dilemma, injustice, inequality or cause in order to make a complex situation more human and relatable. What I am not talking about is the many worthy and factual documentary, video and film pieces aimed at highlighting injustices in education.

The difference is fictionalisation.

Fictionalisation is one of the most important aspects of drama. As viewers we know that the story may, or may not be, based on a set of verifiable facts, but that even where it is a “true story” some of the dialogue and some of the scenes may be fictional ; we accept this. That acceptance permits the filmmakers to tell a story that is more flexible with the facts, and where artistic licence can be used to engage with us emotionally (narrative point of view, non-linear timelines, removal or addition of characters etc.).

When, in the film “In the Heat of the Night”, Mr Endicott slaps Mr Tibbs and Tibbs slaps him back (see clip above), we suspend belief that in the 1950s Tibbs (played by Sidney Poitier) could do this with impunity in front of a police officer. The emotional jolt we get from seeing an equivalence of actions in a racially charged atmosphere is what the filmmaker wants us to feel, not whether such an action ever happened in reality.

Reframing the narrative

But, why is fictionalisation generally avoided by those working in international education development?

Firstly, because, as a sector, educators are hard-wired to be text focused. Books are our holy vessels and reports our liturgy. We communicate by lengthy emails; demonstrate our technical prowess through impressive PowerPoint slides, graphs and tables and eschew emotional appeals except when we are starting Zoom meetings when inevitably we are “excited” (if we’re American) or “pleased” (if we’re British).

Secondly, because as a sector we are ruled by facts and evidence. Yes, facts and evidence are important, but on their own they are insufficient. Government decision-makers do not work with facts alone, they work with politics, of which facts are just a small, and sometimes insignificant, part. The evidence for this is all around us. Look no further than the response to the Post Office scandal – politicians sprang into action, not because the facts had not been known, but because the drama brought the story to life in a real, human and emotional way. As the recently departed Daniel Kahneman said: “Nobody ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story”.

Finally, we are often suspicious of emotion, fearing it to be a sign of bias, poor analytic ability, or a cover for lack of substance. Many of us are moulded in a (Western) tradition that emphasises the passive voice in reports, removes the individual view and uses stories only as case studies to illustrate evidence.

All of that has its place. But, when it comes to engaging with educational injustice, we need to expand our communication tools to reach and inspire broader audiences - the broader audiences that create the open environment in which we can stage our smaller battles.

But, because we downplay emotion, our stories struggle to engage, and there is little attempt to manipulate our audience’s empathy. And, yes, people want to be manipulated. They understand they are being “sold a story” and actively welcome it – not because they want to leave their critical faculties behind, but because they want to be engaged emotionally. Successful stories tell us both emotional and intellectual truths at the same time.

For example, in The First Grader, when 84-year-old Maruge tries to return to school, the use of flashbacks to show the suffering he and his family endured at the hands of cruel British soldiers during the Mau Mau rebellion, allows us to both empathise with him and to more deeply understand his determination in the face of opposition from the ministry of education and local officials (see clip below).

A very short list…

A few months ago, I put a call out for subscribers to this newsletter to recommend the best films about education set in the global south. The response was enthusiastic, but surprisingly limited, with the same films being recommended several times. India stood top with seven recommendations, perhaps a Bollywood influence. But Nigeria with Nollywood – had not a single suggestion ! Overall, the list did not exceed 20 films. This may reflect the limited number of interested subscribers, but it still seems a shockingly low total.

Those that are on the list range from the brilliant to the fairly average. There are films about the injustice of access and retention (First Grader, Not One Less) ; children with disabilities (Taare Zameen Par, Noor); nomadic or remote schooling (Blackboards and Lunana); and cheating and bullying (Bad Genius and School Days).

For a full list of nominated films, links, and a short synopsis of each, plus some suggestions for other short films worth seeing, including northern films, see here.

Why is this list so limited? Why are filmmakers not finding rich sources of stories, or wider audiences, in the everyday experience of schooling in the global south? It cannot be for the want of those stories, or that they have been told too often. It cannot be for the lack of human interest or that there are no stories of educational injustice.

After all, schooling is a microcosm of life. There are complex gender relationships; authority and power issues; the struggle of self within an impersonal system; personal growth and development; friendship and love etc. etc. Above the personal focus there are stories of systemic and social injustice: discrimination, inequality, abuse etc. All in all a terrain that should be rich for filmmakers.

And how to make it longer…

Surely there is an opportunity here to engage a wider audience to understand, appreciate and be moved by the injustices and inequalities in education systems?

If there is, it won’t be done by planning or dictating from media units or communication teams. But, it might be achieved by encouragement and funding, by unleashing creativity – perhaps through funded challenges that inspire filmmakers and creative educators to work together to shine light on an aspect of educational inequity or injustice.

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) set up the inaugural Health for All Film Festival. And although there is no such multilateral equivalent for the Education sector, there was the UNICEF Innocenti Film Festival in 2019 and 2021 (though that was about childhood rather than education).

The French, being the consummate cineastes that they are, have the Festival International du Film d’Education (FIFE) which started in Normandy in 2007 and is still going strong. As you’d expect, the Francophone global south is well-represented ; for example, the 2023 prize winner was a superb Iranian animation called “Our Uniform” and the Feature Length Prize winner in 2022 was a Palestinian film called “Alam” (The Flag) see trailer below.

So, instead of setting up an equivalent to HAFF, perhaps UNICEF or one of the bigger, and bolder, donors / philanthropists in education could invest in FIFE to promote a wider range of submissions and audiences ?

Bolder, because there’s a dilemma : measuring impact would be near impossible, and only a few donors today (but maybe more philanthropists) will invest in something that they cannot measure. The “Bates versus the Post Office” drama is unusual in showing a direct correlation between a drama and political action to address an injustice. In most cases the correlation, if it exists at all, will be more subtle.

For example, changes in attitudes, in understanding, or in social tolerance etc. Can we measure what impact the film “Dead Poet’s Society” had on attitudes to teaching, “Philadelphia” on the popular understanding of AIDS, or “Gandhi” on views of British colonialism in India ? But, their popularity was important in signalling a willingness in society to hear about those stories. And, possibly, they contributed to changing social attitudes towards teaching / AIDS / empire ….

But, move quickly, the ground is shifting ….

But, while we debate this question of the representation of education and education injustice in film, the world of filmmaking is changing rapidly. Until recently, aside from the “cultural barriers” cited above, of educators’ preference for the written word over film / drama, the other major barrier has been cost. Making films – even the kind of project documentaries common in our sector - has been prohibitively costly. That is all changing with the increase in digital power of smartphones – and the massive advances in AI.

Since 2015 film makers have been using smartphones partially or fully to make movies. Steven Soderbergh was one of the first with “Unsane”. More recently, Victoria Mapplebeck won a Bafta in 2019 with a short film, shot fully on smartphones, called “Missed Call”.

The recent launch of the Open AI Sora tool that can make videos using written prompts (see Air Head, below, as an example of a completely AI made film) open huge possibilities for filmmakers. Will educators be ready to take advantage of that opportunity ? The development of synthetic violin strings did not make everyone a musician : likewise, technological advances will not make everyone a filmmaker - the skills of filmmaking still need to be learned.

But, the time to learn, and the assistance that could be available to accelerate that learning, mean a potentially much larger and more diverse set of people could become involved in that process. It means that teachers, children, parents, educators could become the filmmakers of the future.

So, here’s a challenge to donors / philanthropists : let’s combine these two issues – putting more emotion and fiction into amplifying and, hopefully, redressing education injustices….and do it using new low cost technology.

Is there a donor / philanthropist willing to put some serious money into a challenge fund to produce feature length films about aspects of education inequality in the global south, created by educators in the global south, using smartphones and AI ?

In the spirit of sharing learning, the challenge fund could co-opt some well-known filmmakers to review proposals and work with successful candidates. The outcome of such an initiative could be a number of nationally or internationally recognised films about education injustices employing fictionalisation, drama and emotion - bringing those causes to a wider audience and inspiring change and progress.

Who knows, could there even be an Oscar in sight ? !

That would be a measurable result to bring a lump to the throat, a tear to the eye and….. spark the impulse to action !

News

UNESCO has released a companion report to the Global Education Monitoring Report 2023 - the 2024 Gender Report which focuses on girls access to and use of technology in education. Girls represent only 35% of STEM graduates - a figure that has not changed in 10 years.

USAID has released the US Government Strategy on Basic Education 2024-2029. It has four Approaches (Localisation ; Data and Evidence ; Capacity Building ; Equity and Inclusion) and three Objectives (Learning Outcomes ; Expanding access for the most marginalised ; Collaboration and leveraging resources).

The President of the Republic of Zambia, His Excellency, Mr Hakainde Hichilema has taken on the role of Champion of Foundational Learning (FL) in Africa in Africa’s Year of Education 2024.

Development

Duncan Green, Oxfam staffer, LSE Professor and originator of the excellent blog and podcast, From Poverty to Power (FP2P), has retired from Oxfam and will stop publishing FP2P. He’s been a hugely influential voice in the development space - just look at some of the comments on his announcement. He’s a very direct and often funny commentator, with a wealth of experience and a no-bullshit attitude (e.g. his characterisation of the “enshittification” of Twitter).

As he’s bowed out he has done some excellent short pieces on what he’s learned from 30+ years in development. Find time to read “Learning from Humiliation, Shame and Failure” or “Some of the Big Hits and Misses from 16 years of blogging on FP2P”. There are lessons there for all of us.

And still on the theme of retirement, LeAnna Marr, who has been with USAID Education for the last 25 years, has announced her retirement. She has done a lot to keep Education high in the Administration’s sights, including recently by spearheading the awareness of lead poisoning issues. Her announcement message has a link to some heartfelt comments by US Administrator, Samantha Power.

Voices from the front

An interesting piece in the UKFIET blog series about student leadership in Bangladesh by Zahirul Islam. Adds to the awareness of student voice and all the different ways that can be realised in schools as well as the power of engaging students in the ways this article outlines.

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

A new network, POLED, has been set up to promote the understanding of the politics of education - a welcome focus away from technocratic solutions only. You can access their speaker series here. Or follow them on X @polednetwork

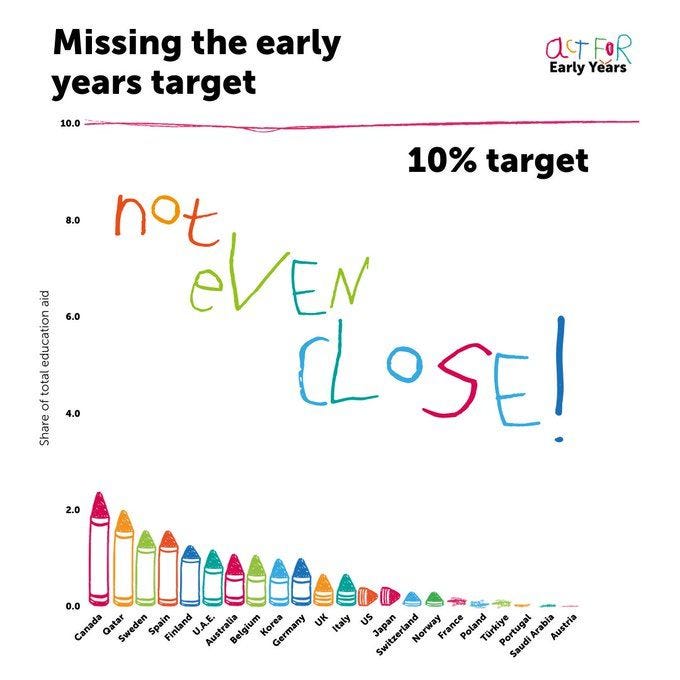

New Research for TheirWorld by the Asma Zubairi and Pauline Rose at the REAL Centre on funding of Early Childhood Development makes for unhappy, but not surprising, reading. The chart below says it all.

…and finally

Still on the theme of the impact of drama, a clever UNICEF video on the importance of girls’ education done in a lovely split frame style. In 90 seconds it conveys more succinctly and pointedly all the arguments that written papers take 50 pages to say. Very powerful.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.