Re Education : Issue #8 - Praying for Scale

A newsletter about international education development

Introduction

This month’s newsletter looks at two critical issues facing education systems in crisis : the huge number of out-of-school children, and the difficulties of scaling successful initiatives.

The Luminos Fund in Liberia may have an answer to both : a programme called Second Chance that condenses the first three years of primary school into just 10 months and which has been designed to scale quickly. I examine the programme’s claims and look at why prayer may be the only answer.

For those interested in the messy realities of how policy and practice collide, how evidence is ignored …and how it is used, I have also included the transcript of my interview with George Werner, Minister of Education, Liberia 2015-2018. He’s been in the hot seat and thought hard about these difficult questions. Worth a read.

My thanks to the staff at Luminos Fund who were open, transparent and helpful : willingly submitting to the spotlight and the scalpel !

Andy Brock, June 2024

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

The only dreams impossible to reach are the ones you never pursue. Michael Deckman

A Hope and a Prayer – Scaling Success in Liberia

The Background

In the league table of countries with the most children out of school, Liberia isn’t at the top, but it’s not far off. Afghanistan with 62% of children out of school and DRC with 48% have more. Liberia, according to UNESCO estimates, has at least 30-40% of primary children out of school and in 2015 UNICEF reported that it had the highest proportion of out-of-school children in west Africa.

Any initiative that can make a significant dent in those numbers needs to be examined seriously. Without a high level of basic literacy and numeracy no country can hope to develop.

In 2016 The Luminos Fund, in a joint initiative with the Government of Liberia, started an accelerated learning programme, called Second Chance, aimed at addressing Liberia’s out-of-school problem. The Second Chance programme takes kids who have never been to school, or been out of school for two years, and speeds them through the first three years of the primary curriculum in just ten months.

George Werner was the Minister of Education when the programme started. He says : “The Second Chance Program adds value to teacher training and helps reinforce the government system by bringing on board passionate teachers”. Since leaving office he has joined the Board of Luminos and now advises on their programmes in Liberia, Ghana, Ethiopia and The Gambia.

In Liberia the results have been impressive. In 2023 an Impact Evaluation conducted by ID Insight, using an RCT methodology, revealed that reading outcomes had increased to 30 words per minute (wpm) compared to just 7 in a control group ; numeracy improvement has been dramatic too, doubling correct answers compared to a control group. The programme ensures that children who graduate have a transition pathway into a local government school and a grant from Luminos to smooth the process.

The tables above show Baseline and Endline Oral Reading Fluency results.

The ID Insight report concluded that :

“The obtained results exhibit high levels of statistical significance, thus confirming the program's effectiveness in enhancing the reading and math skills of participating children.”

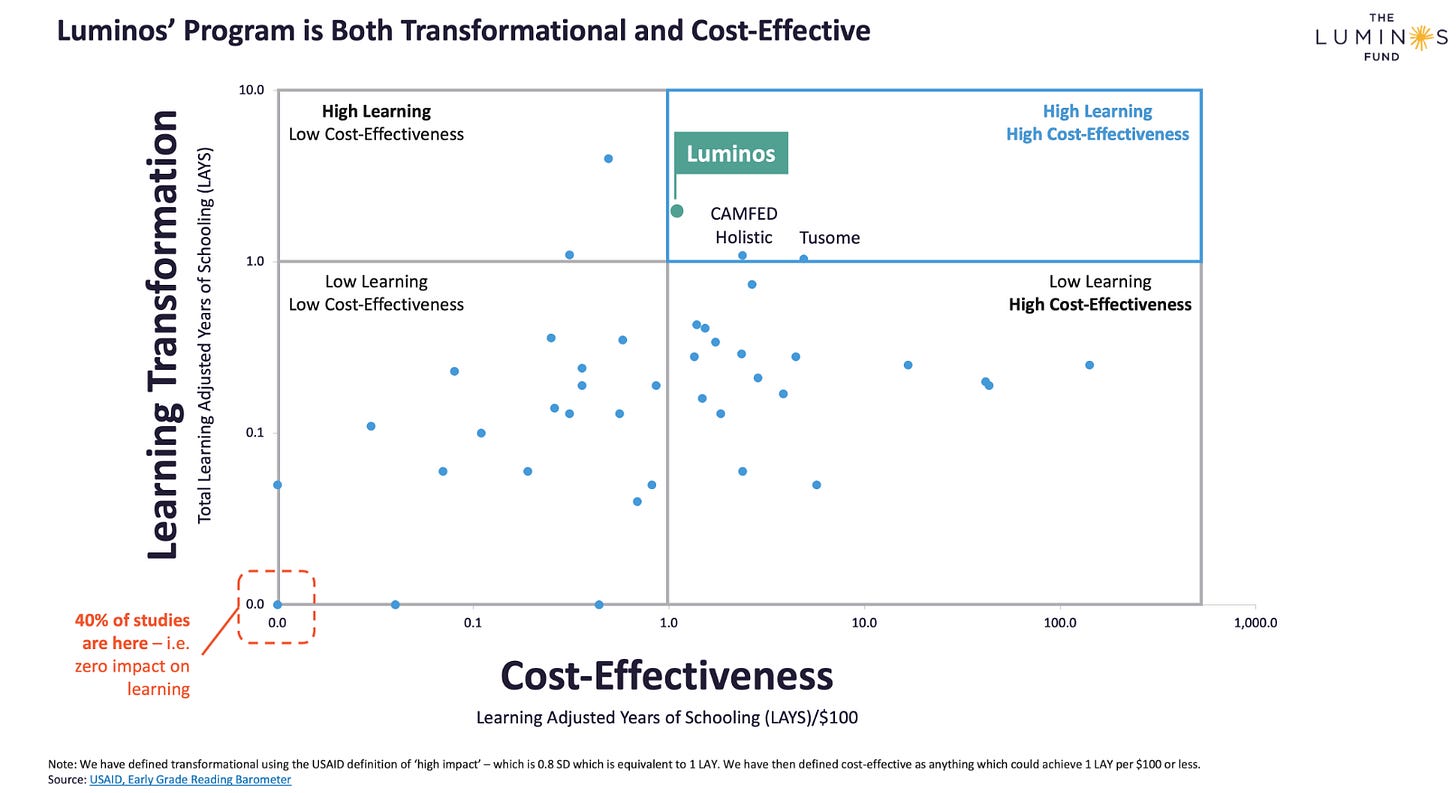

The programme is also one of only a handful that appear in the top right quadrant of an effectiveness / learning matrix drawing on data from the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel 2020 “Smart Buys” report.

Source : Luminos Fund

The programme achieves all this at an average cost per child of $180 using community facilitators who earn 25% less than government teachers but who receive intensive training and support.

The Second Chance programme has successfully expanded its reach from 2,000 out-of-school children in 2019 to over 6,000 in 2024. But, how replicable is the model ; at what scale ; and at what cost ?

The Scale of the Problem

There are an estimated 60 million primary children out of school worldwide. In Liberia the estimates of the numbers of out-of-school-children vary dramatically according to UNESCO – from a median of 260,000 to 371,000 ; 30-44% of the primary school age population. A programme that provides an effective solution to this problem demands attention.

The country has been through a turbulent period of civil war, the Ebola crisis and the COVID crisis all of which have severely affected education provision. Geographical barriers and poverty make programmes like Second Chance even harder to implement.

When George Werner was appointed Minister of Education in 2015 he toured the country assessing the depth of the issues. He says : “I knew I had just two years left of the second term of an outgoing president. I was always concerned about what one could actually accomplish in two years. So, I went in as a bulldozer, which has its advantages and disadvantages. I took on a lot in terms of reform, some of which were radical in nature and began to be very controversial.”

The Second Chance programme fitted that radical approach – to move fast and fix things.

The Scale of the Approach

There are three main factors behind the success of the Second Chance programme says James Kiawoin, Luminos Country Manager : a play based curriculum, quality training and a clear route for kids into the formal education system.

Luminos classes are often in classrooms donated by a local school, or in a local house or a back yard. The curriculum, approved by the government, is play-based and keeps kids engaged and motivated. Kiawoin says “Classes are pretty noisy and cheerful, there’s lots of singing and laughing”. That energy is needed – school days are an intensive 6 hours and the programme is a straight ten months, no breaks.

Many innovative programmes try to break from the monotony of rote learning, but few are able to do so using community-recruited and largely untrained facilitators as teachers. Kiawoin says the typical Luminos teacher is a high school graduate from the local area – with an average age of 25. Recruits get intensive training to start and then 25-30 days of coaching a year, mostly on site in their classes. The quality and frequency of the support teachers get is a big motivation - and a compensation for the lower salaries they accept.

So too are the well-designed career incentives. Those who do well can become government teachers through a pathway agreed with the Ministry of Education – providing much-prized job security. A portion of the facilitators get promoted to be coaches themselves each year. Coaches are attractive to national or international NGOs working in education, or to business or academia, even the Ministry itself.

In a true grassroots-to-golden-palaces story, Abba G Karnga Jr. joined the Luminos programme in 2017 as a programme manager and coach, daily supporting teachers in the field. In April 2024 he was appointed Assistant Minister of Basic Education for Liberia, not a bad friend for the programme to have.

The Scale of the Money

All this is not expensive, but it’s not cheap either. The cost per child is about $180 for the ten-month programme. That compares to $85 for a 7-month accelerated learning programme in Nigeria that found only modest learning effects ; or a heavily caveated $157 aggregate for three programmes in Ghana. The cost-effectiveness literature in this area is light – Luminos is adding to the stock.

Putting these figures in perspective, the Liberian government budgets about $50/60 per annum per primary pupil. It’s not a fair comparison because that is full schooling not an accelerated programme, but it’s probably the comparison that counts the most to the Treasury. Three years at $50 per head, $150 vs $180 ; there’s little in it, except the outcomes which are greatly different.

At this cost, and taking the (conservatively) estimated 260,000 out-of-school primary children figure - could an expanded Luminos programme reach them all ?

Dr. Kirsty Newman, Luminos VP of Programs, is at first a little thrown by the question ; it would be a 40-fold increase from the current programme. She comes back with a brave “Yes, I think it is”, though quickly adds caveats around capacity and government willingness.

Reaching all 260,000 children at about $180 per child would cost $45.8m (though it could be considerably less than this if a full-scale approach was taken). Spread over five years that’s c.$9m per annum, almost a quarter of the annual budget for primary education in Liberia ($45m in 2023), but small beer for a multilateral donor like the World Bank.

But, the barriers to getting to this kind of scale quickly (five years would be lightning fast) are less financial than structural and aspirational. To embark on a programme of that scale and speed, muses Kirsty Newman, would require considerable political focus and agreement, not just with government but donors too, not to mention world-class project management skills.

She adds : “In fact, using our current model we estimate that we could increase four-fold each year assuming about 20% of our community facilitators can move up to being coaches each year and each of them can coach twenty community facilitators”. That’s twice the rate of increase seen in the last five years, but, if it could be done, it would mean reaching 260,000 children could be achieved in less than 5 years

James Kiawoin points to three other difficulties : the capacity of the physical infrastructure to absorb large numbers of children graduating from the Second Chance programme, the government’s concern about reducing the number of overage children in schools (by definition most children in the Luminos programme are overage) and the high costs of reaching dispersed populations.

Can Prayer be Scaled ?

The pitfalls that many other programmes fall into – lack of ownership, poorly designed incentives, costs that are unsustainable – have largely been avoided by Luminos. Spin-off benefits also abound ; some government school teachers have adapted their practice after seeing the Luminos curriculum in action and Luminos kids entering government schools rub off some of the programmes successes on others. At a minimum, for 6,000 Liberian children it is giving opportunities which are life-changing.

Nonetheless, if your problem is 260,000 out-of-school children, does reaching 6,000 constitute success ?

George Werner counters : “I wanted this programme to serve as an example not just for Liberia, but for the region. I wasn’t expecting Luminos to take on the entire challenge, but to demonstrate that children can learn in a joyful, playful way with a passionate teacher”.

A fair point, yet, the success of the Luminos programme neatly illustrates the dilemma facing all externally supported education interventions – even ones jointly developed with government, even ones based on the most robust evidence of “what works” : they are based on a hope and a prayer.

The hope is that the intervention is successful, a proof of concept ; the prayer is that government will adopt it, fund it and roll it out across the country. In most cases that prayer goes unanswered.

George Werner knows how this works on the ground. He says : “You have to understand that policy is not dictated by evidence, especially in physically constrained environments with competing needs. You have post-civil war, post-Ebola, and post-Corona environments where there are competing needs. Sometimes evidence is ignored. The other aspect is the political aspect where human capital development is not as tangible to a politician as building a bridge or a house”.

In a perfect world, the plans and finance to scale a successful programme should be designed in from the start and be part of an explicit agreement with the Ministry of Education, combined with committed funding from the Ministry of Finance. That almost never happens. Instead, all efforts focus on the proof of concept and little thought is given to how success would be scaled : hope beats prayer. The question that should be asked is : if this initiative is successful what would it take to scale it and how should that be designed in from the start ?

As a demonstration of the positive impact of joyful learning the Luminos programme has proven its designers’ ambitions. But, although it has the potential to scale quickly, that potential remains untested. Increasing from 2,000 to 6,000 children in 5 years is very different from expanding by 24,000 in one year. Scaling massively means risking quality or even the integrity of the model itself. Until that is tested, its usefulness as a model to replicate in contexts where hundreds of thousands of children are out of school remains unanswered.

Kirsty Newman says if they could get the funding to go to scale, they would love to try. She points out that scale would happen through the African-led organisations already embedded in the communities that Luminos works with. And she’s confident that the training model would be effective and keep costs low.

This is where the drive from the Ministry of Education coupled with boldness from donors could make a step change in the Liberian education system. George Werner is hopeful. He points to the time he persuaded the Minister of Finance and President to invest in his “Getting to Best” education programme by convincing them that their infrastructure projects would fail without a strong human capital base. “With a combination of political advocacy and strong evidence you can persuade the decision-makers”.

The Liberia Second Chance programme has met, even exceeded, the hopes of the Government of Liberia, parents and its participating children.

But, can its prayer be answered ?

Further information on the Luminos Liberia Programme

See here for the full interview with George Werner

News

UNICEF reports that more than 10m children in Nigeria alone are out of school, despite free education. Nigeria now accounts for 1 in 5 of all out of school children worldwide.

Alex Smith, a USAID contractor, resigned when his presentation on maternal and child mortality in Gaza was cancelled. Worth listening to his very measured responses in this interview.

The war in Sudan continues to disrupt education. Save the Children have reported a fourfold increase on attacks on schools and warn the crisis is becoming one of the worst in the world - 18m children have missed school for a year.

Development

Ken Opalo, who writes a great newsletter called “An Africanist Perspective” (I recommend subscribing), has written an interesting post, critical of current donor policy, on how Melinda French Gates can use the £12.5bn she is putting, post divorce, into her own philanthropic journey. Education and the private sector are two areas he singles out. He also articulates something I’ve long been puzzled by :

The entrepreneurial backgrounds of most philanthropists should have meant greater focus on private sector growth and a much higher appetite for risk taking on project design. Yet the international development “field” completely tamed these impulses.

Voices from the front

Heartening to see the continued innovative attempts to provide education for girls in Afghanistan. A charity called Charmaghz led by Freshta Karim is doing just that through mobile libraries. See this LinkedIn post.

The BRAC Social Innovation Lab has published a Failure Report 2022-23 using a number of project stories (none education). Good marketing : few in development admit to failure and using the word piques interest. In fact, it would more accurately be described as a series of adaptive programming lessons, but that wouldn’t have generated the same interest. Nevertheless, a good read.

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

A very interesting paper published by Arif Naveed More Snakes Than Ladders: Mass Schooling, Social Closure, and the Pursuit of Tarraqi (Social Mobility) in Rural Pakistan using a study in rural Punjab to demonstrate the limitations of education, on its own, to deliver economic empowerment and social progress. The fact that, worldwide, education provides clear personal and social returns cannot be disputed. But Naveed’s paper reminds us that this is not always and everywhere the case - and in some cases the education system can be actively used to hinder social advancement. Social and institutional barriers also need to be removed.

Jessica Leight posted an interesting thread about whether NGO’s are more effective than governments at delivering programmes. The specific China paper mentioned seems pretty lightweight to hang anything on, the other material cited is more convincing. But, is this really saying anything more than NGOs are nimble compared to governments ? Quelle surprise !

…and finally

For those contemplating summer holidays, a timely piece of research in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, the snappily titled : “Transient decreases in blood pressure and heart rate with increased subjective level of relaxation while viewing water compared with adjacent ground.” In other words, watching a river, lake, loch or the ocean is likely to relax you. There’s a reason the best holidays are at the beach !

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.

Thanks for this Andy - I work with Luminos on their accelerated learning govt partnership programme in The Gambia so am always interested in reading and learning more. Certainly over this last year, having trained the facilitators three times and heading out to do the same again next week, I am awe by how hard they have tried to learn and use new techniques that are SO different to how they were taught themselves. They are a marvel. I’m new to your newsletter but am currently going through your catalogue! Thank you.