Re Education : Issue #5 - The Process of Inclusion

A newsletter about international education development

A Hopeful Journey

Are children with disabilities in Zimbabwe better off now than 30 years ago ? (And how many cows does it take to get all children with disabilities into school ?)

Our guest interview this month poses this question to Professor Tsitsi Chataika, a well-known and very experienced Zimbabwean inclusion specialist. In 2019 Prof. Chataika authored a comprehensive review of disability inclusion in 32 countries in Africa on behalf of the African Union.

We discuss her insights on how education systems change with respect to inclusion...and how they resist that change.

As Prof. Chataika notes, the international community generally, and donors specifically, play important roles in lending supra-national legitimacy to the work of national disability activists. But, their support can also crowd out the financing that should be coming from recurrent budgets.

Just as importantly, how engaged are people with disabilities and grassroots disability organisations in the process of designing interventions and deciding how funds are spent ? Donors tend to favour larger organisations (to reduce transaction costs) who then act as gatekeepers deciding who will participate – often using criteria that are more about risk avoidance than maximising impact.

The example of Zimbabwe is a positive one, and there are encouraging signs too from other countries in Africa. But, these gains need to be fought for, they will not simply be granted. Appreciating the journey to come is helped by understanding the road already travelled.

Andy Brock, March 2024

Scroll down for Guest Post / News / Development / Voices from the Front / Voices from the Rear / Fun Stuff

Subscribe for free and receive each issue of Re Education automatically to your inbox.

Guest Post

In conversation with ….Prof. Tsitsi Chataika

Tsitsi Chataika was, until recently, an Associate Professor of Inclusive Education at the University of Zimbabwe. She now works for CBM Global Disability Inclusion, a disability rights organisation, as the Disability Inclusion Adviser.

What’s your experience of advocating and working for children with disabilities in educational settings in Zimbabwe? What changes – positive or negative - have you observed in the last twenty or thirty years?

I have been involved in disability and education since 1993. I had an opportunity to teach in a special school. What I can say is, back then, disability was not really an issue to bother about in terms of inclusion – the key issue we were concerned about was how best to teach children in special schools.

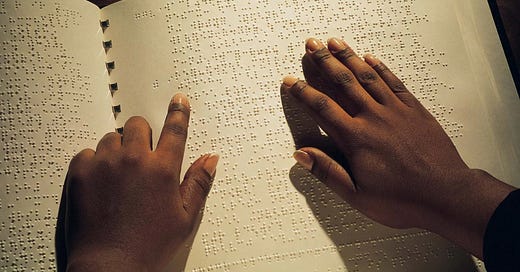

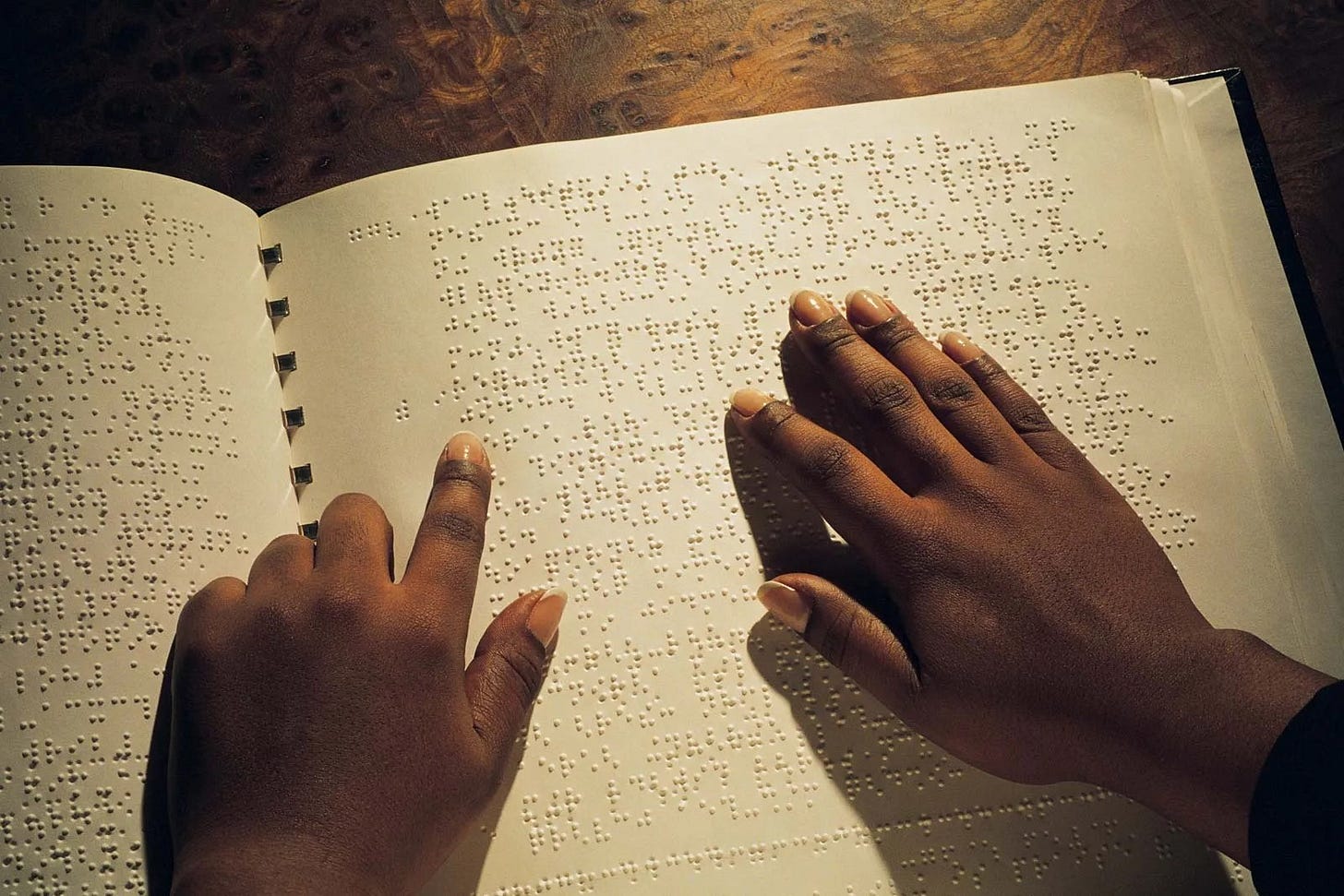

For most teachers in special schools, you would train to become a mainstream teacher, and then train as a specialist teacher. At that time, I was teaching learners with visual impairments.

Once some of the learners began learning in mainstream schools, the community began to realise that they could perform as well as other learners, as long as they had support. But, this took time to change. For example, I had a colleague who had a visual impairment and was sent to a mainstream school where the community was not very impressed. They said “How can this special teacher teach my seeing child ?” So, it took time for communities to accept.

That change you described, where it became accepted that children with disabilities could be accommodated in mainstream schools, how did that happen ? You talked about one aspect – social attitudes – but what about other aspects such as the attitude of the Ministry of Education ? Who drove that change ?

Yes, I think it was to do with international legal frameworks that were becoming well known e.g. the Salamanca Framework and that started to change the status quo and mindsets. Although it was not part of government policy then, the Ministry of Education started following up with circulars with regards to supporting children with disabilities. That made schools consider how they could support learners with disabilities. But, the real challenge was the capacity of the teachers themselves, the mainstream teachers, because they didn’t have any training on educating learners with disabilities.

For me, I’ve always said inclusion is a process. Also, people needed real examples, and it wasn’t until children with disabilities started going through the mainstream system that we had examples of how children could be successfully supported.

Were the policy positions adopted in this period unfunded ? Did the Government say “Do this” – but not provide funding ? Did legal frameworks and policy positions create imperatives ?

Yes, but there was a lot of advocacy that contributed a lot. Disability advocacy in Africa emanated from Zimbabwe.

In section 83 of the Constitution there is a focus on persons with disabilities. It says all the right things, but ends with the phrase like “funds permitting”, so it’s a qualified right under the constitution.

Mostly, the support for children with disabilities is coming from donor agencies. Several donors and NGOs have been supporting this area with funds.

Where are countries in Africa supporting children with disabilities in education well / badly ?

Most donor agencies working in Zimbabwe are also working elsewhere in Africa. There are disability rights movements across many different countries – e.g. Uganda is quite pushy, and in 2010, they had five MPs with disabilities. There was good representation from grassroots up to national level. They were empowered to advocate. They have produced several reports on disability – quite inclusive approaches compared to other countries. Also, in Malawi – they have fewer resources, but you can see efforts that have been put into supporting mainstream schools – supported by donors.

Are there countries making little effort ?

It varies a lot – each country is a learning point. Francophone countries tend to struggle. Religion and culture have specific impacts in particular countries.

Is there a pan-African Disability Organisation specifically for Education ?

In SADC – there is the Southern Africa Federation of the Disabled and there are many advocates within SADC. The Africa Disability Alliance operates at a continent level – and has done quite a lot – not just for education. The African Union has also done quite a bit, in collaboration with others. They have a Disability Desk.

Reflecting on Teacher Training and awareness – are newly graduating teachers better trained now to teach children with disabilities ?

I can see progress. When I started there was only one Teacher Training College covering disability in education, in Bulawayo. Now, almost all universities focus on inclusive education.

Teachers and administrators have realised issues of physical accessibility, and they have been addressing this. Now, the focus should be in the classroom – how to support children to access the curriculum. Here I am thinking of curriculum differentiation, the actual learning so that learners with disabilities have positive learning outcomes.

The issue is the practicality of dealing with for example, dyslexia. What skills are needed, what support etc ? The curriculum does not help put it into practice, so there’s a discrepancy between what teachers learn and what they implement.

I have personal experience of this : shortly after training I was given a class with learners with multiple impairments – and I was not ready for that. I had trained to become a teacher for learners with visual impairments. Then I was faced with a child who is blind, a child who is a wheelchair user, a child who is deaf….so, I said, okay, how do I deal with this? I had read the theories, but how do I deal with the practical ? So, this is the situation, how do I communicate with these children, you start thinking and learning and changing everything you thought you knew.

And you need that kind of innovative teacher who says “Ok, I’ve learned things, but this is the situation, how then do I make sure that learning takes place ?” That’s why you need to teach teachers to be more inquisitive and think outside the box so that they can better support children.

If teachers now find themselves in this situation – where can they get support ?

In Zimbabwe we use a cluster model. The Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education puts schools into clusters, where schools can share and support each other. There may be a model school for inclusion for example, other schools can attend training and learn from this school. They can learn how best to deal with issues of inclusion from others with experience.

Which is more important now - funding or attitudinal change – what’s the priority ?

It’s less about funding now, more about attitudes. A lot has been done, but there’s more to do. We need government to be deliberate in terms of funding. At the moment most funding is coming from development partners. We’re at a stage where I believe that the Government should adopt inclusive education as a national strategy for providing education in Zimbabwe. I believe what is good for learners with disabilities is good for everyone. Funding is still a big issue – and it’s more political. Lack of funding comes from lack of understanding of the needs of learners with disabilities, which leads to less prioritisation.

A lot of changes took place from 2018 to now : there are more policies and greater focus. There is now a Department of Disability Affairs and the current President has a soft spot for disability issues and I think people need to take advantage of that and push the agenda further.

I’ll be very happy if Section 83 of the Constitution is reviewed and they remove the “If funds permit” phrase.

What else needs to be done ?

There’s the issue of home-school partnerships – it has helped within communities. There are disability inclusion committees, spearheaded by parents. They count and register the number of children with disabilities.

I heard of one Chief in Matabeleland South where he said that if parents do not send their child to school, they must pay a cow as punishment ! So, this resulted in most children with disabilities going to school.

Then, there’s the issue that when the Constitution was revised, the Government took Sign Language as one of the 16 languages in the country. There is a curriculum and syllabi for Sign Language in infants and junior (primary) and secondary schools. There are now several organisation and universities providing training for sign language, but we need public recognition of the language.

What’s the one thing you would do now if you had the power ?

Open up every school to become an inclusive school so children go to the nearest schools. We don’t want children to travel long distances, otherwise we will be infringing their right to education within their communities, which is their constitutional right.

Tsitsi was also interviewed last year on Richard Ingram’s podcast Goal4 Education for All, which has a wide range of interviews with leading lights in international education. Tsitsi Chataika on Training Teachers and Universal Design - Goal 4: Education for All | Acast

News

Some snippets of recent news / events that seem worth sharing.

As the senseless killing and starving of children continues in Gaza, our stubborn ounces must add weight (posted by Lindsay Hilsum).

Stubborn Ounces - Bonaro W Overstreet

(To One Who Doubts the Worth of Doing Anything If You Can’t Do Everything) You say the Little efforts that I make will do no good: they never will prevail to tip the hovering scale where Justice hangs in balance. I don’t think I ever thought they would. But I am prejudiced beyond debate in favour of my right to choose which side shall feel the stubborn ounces of my weight.

Development

Is education a force for peace and development ? Are better educated nations more peaceful ? We all wish it were true, but is it ? Russia and Israel both have highly educated populations…..and that’s before we even open the discussion on colonialism or review the educational levels of pre-Nazi Germany. One interesting piece of research shared with me is this 2019 paper : Does Education Lead to Pacification ?

Although the paper finds a positive link between education and peace, it contains a critical caveat :

An emerging scholarly consensus seems to be that education has a general pacifying effect. However, this general conclusion is challenged by recent evidence showing above-average levels of education among terrorists and genocide perpetrators.

Where there is perhaps less dispute is the role of education in picking up the pieces post-conflict. See this recent contribution from David Armstrong for example.

Lots of social media traffic recently on Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) sparked by this article in The Economist. Some choice quotes from Arvind Subramanian, a former chief economic adviser to the Indian government. The rise of RCTs, in his view, is due to the influence of a :

“very incestuous club of prominent academics, philanthropy and mostly weak governments. That’s why you will see RCTs used disproportionately in sub-Saharan African contexts, where…state capacity is weak.”

A more nuanced thread from Amber Peterman presents a balanced case. Worth a read – most educators have to deal directly or indirectly with RCT’s – so it’s important to understand where they add value and where not.

And, on the subject of the real value of evidence – here’s a timely tweet from Ben Phillips, well-known author of “How to Fight Inequality” (a great read) on the “Evidence Paradox”.

Voices from the front

Continuing the theme of disabilty, Sightsavers published a blog on empowering people with disabilities to design the programmes that support them.

Matt Jackson of ADD drew my attention to the following website : The Decelerator. A really interesting and practical service aimed at closing down organisations, transitioning leadership or phasing out support. It’s largely focused on CSO’s, but it’s a great idea and the site is full of helpful tools and resources that would be applicable to any organisation ending a project, a stream of support, or localising control. Something I suspect there needs to be much more talk about in years to come.

Finally, a UK focused piece, showing failure to act on evidence knows no geographic or developed / underdeveloped boundaries. The Times Educational Supplement (TES) has done a fascinating interview with Kevan Collins, the man appointed to get the English education system back off its knees after COVID, and how expert advice, consultation and first rate planning all succumbed to political weakness and the short-sightedness of the Treasury. Covid and education: why the catch-up cash never came | Tes

Voices from the rear

(Gray and Published Research)

The UN Secretary General launched the Report of the High Level Panel on the Teaching Profession . It’s essential to highlight the importance of teachers, good too that the top brass get behind the message, but…… there are 52 recommendations and 7 more recommendations on actions to be taken. If everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.

Some good news : education funding in Sub-Saharan Africa is increasing in real terms – modestly, 2% on average, not enough to dent the Foundational Learning issue, but better than the 23% drop in international aid to education in Africa. See this link to the Education Finance Watch special report for the African Union Year of Education 2024.

UBoraBora has just launched a new fund for research into Foundational Learning. Grants of up to $100,000 are available. If that interests you – this is the link. So, in five years’ time we might know a lot more about “what works” in Foundational Learning – then what ? It feels like there’s a reluctance to touch i.e. fund / put resources into the difficult, political conversations that are needed now to actually get schools funded and supported, and kids learning. But, research is uncontroversial, especially compared to taking action.

Hugh MacLean in his essay “The Ground Beneath Our Feet” (pp57-59) gives an excellent and concise summary of the level of effort, political will and resources needed to achieve mass literacy in China, the Soviet Union, Tanzania, Cuba, South Korea and Vietnam. It’s this level of effort that is needed today, not piecemeal research funding no matter how useful.

What do you think ? Take the anonymous poll below. Do give your opinion rather than your “tribe” (researchers, consultants, policymakers etc.). If you think this is too simplistic - leave a comment below. I’ll publish the results in the next issue of Re Education.

Fun Stuff

Not quite “fun” this month – more, refreshing. James Timpson runs a UK chain of small shops doing key cutting, dry cleaning and shoe repair. Over 10% of their workforce have criminal convictions, a conscious policy to give opportunity to those excluded by other organisations. You could apply what Timpson says to any business, to NGOs, to a government department, to academia. The most telling phrase is : “where people are happiest we make most money”. But, it could be “we do the best work” “ we do our best research” “we get the most repeat business”. So much energy is put into measuring and managing that could be put into facilitating and supporting – and, if it was, people would be happier.

If you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, please pass on, by clicking the share button below. Subscription is free - subscribers receive each issue of Re Education automatically.